Destiny Crockett: Exploring Art, Poetry, and Black Cultural Preservation

Destiny Crockett is a scholar, artist, and Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Rutgers University, blending Black feminist theory, visual art, and poetry.

Destiny Crockett is a scholar, artist, and Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow at Rutgers University, blending Black feminist theory, visual art, and poetry. With a Ph.D. in English, her research on Black girlhood and cultural production shapes her creative practice. Through workshops like Staged So Black at The Colored Girls Museum, Destiny fosters intergenerational dialogue and reflection on Black cultural narratives, connecting Black women and girls through art and writing. A St. Louis native, she holds a B.A. in English, African American Studies, and Gender and Sexuality Studies from Princeton University.

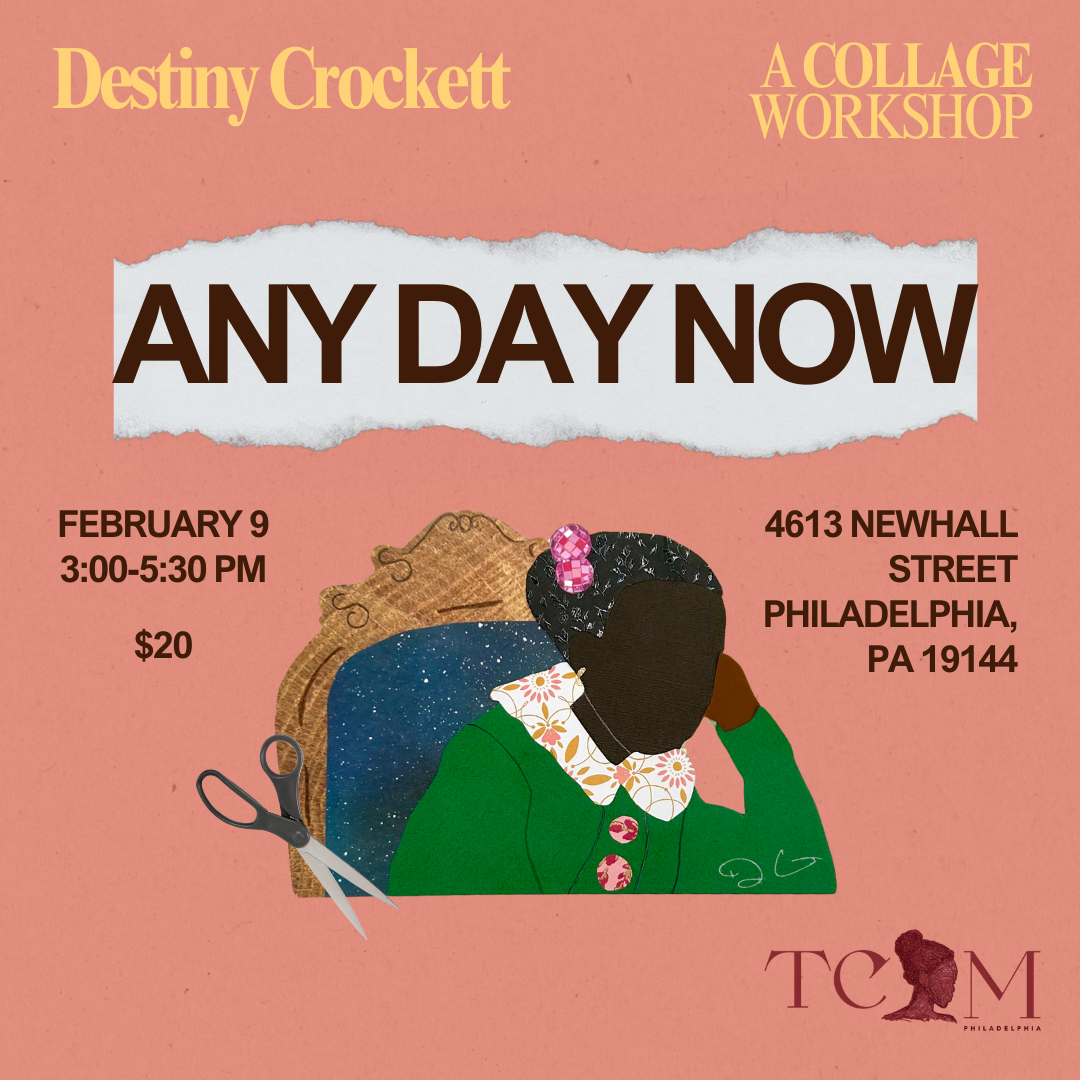

Workshop

In Staged So Black, Destiny invites participants to explore the intersection of visual art and poetry. Through a hands-on, interactive approach, she sparks dialogue between these mediums, encouraging attendees to engage with Black cultural narratives in deeply personal ways.

The workshop is open to all ages, with free parking available. The museum is a 3-story house turned museum and does not have an elevator. Situated in Germantown, the museum serves as a key cultural hub in a historically Black neighborhood. The workshop emphasizes the importance of creating spaces where people of all ages can engage with art, particularly within Black communities.

The Colored Girls Museum A vital space for Black art and storytelling in Philadelphia, The Colored Girls Museum preserves and celebrates the narratives of Black women, offering a cultural touchstone in the heart of Germantown.

Get to know Destiny Crockett through this brief Q&A, where she shares insights about her work, creative process, and the vision behind Staged So Black:

Your work bridges academia and community art. How do you see these spaces informing and challenging each other in your practice?

My study of African American literature and visual art didn’t begin in the academy, so I always knew my engagement with the traditions I love would not remain in the academy. My mother, who did not have a college degree, taught me to read using the poetry of Langston Hughes. My grandmother is an exacting genius in the kitchen, and food, to me, is a form of art. I spent a ton of time at the public library as a teenager, reading whatever I saw by Black authors—Shange, Morrison, Baldwin, Jacqueline Woodson. I borrowed my auntie’s books by Wahida Clark and Nikki Turner, even Zane. I have been a reader of everything Black, and a poet and a visual artist ever since I could remember.

The academy introduced me to names, dates, events, and historic contextualization, and I have been privileged to have graduated from two of the most well-resourced universities in the world and to benefit from caring mentorship, but formal study is not everything to me, especially because half the purpose of elite academic spaces is exclusion in this meaning grinding machine that is capitalism. That doesn’t change because of Black presence in them. Often, very privileged Black people can even magnify that exclusion. So as someone who was able to learn the game of applying to universities in large part because of multiple college access programs aimed at helping people become the first in our families to graduate from college, there’s always a chasm for me, culturally. I have taken students I’ve taught in university settings on field trips to TCGM, though–and they’ve loved it. One former student even came to my first poetry incubator and brought a friend. In the tradition of Toni Cade Bambara, and lots of everyday Black women whose names haven’t been archived, I think the role of the formally educated cultural worker is to make Black people their business, wherever they are, and to give something back to the places in which we live. I’m from St. Louis, not Philly. I have moved here, and taken up space. I have to give something to Philly and be present with the people. This is a really tiny part of that.

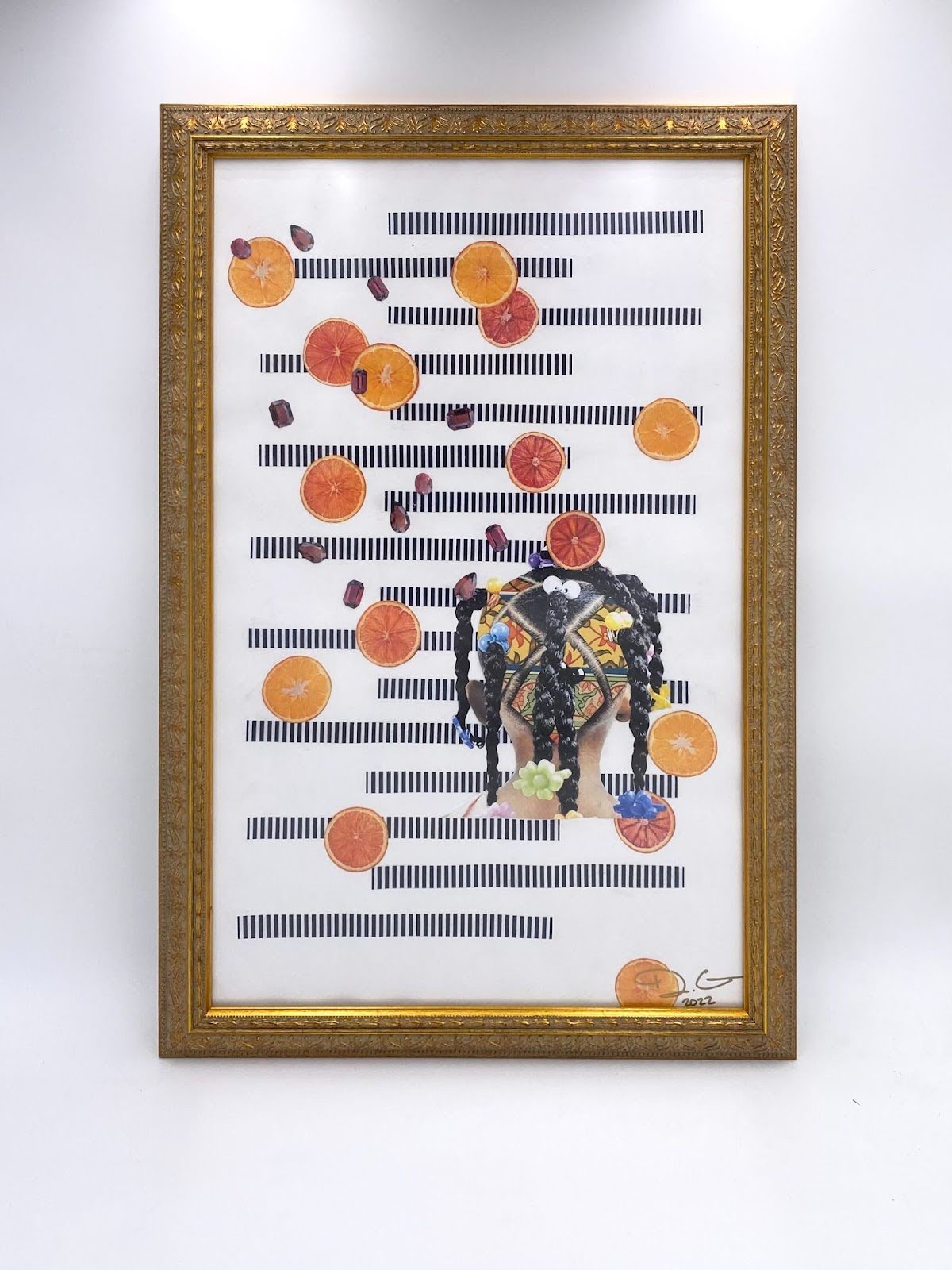

2. Your hand-cut designs often explore themes of girlhood and Black women's literature. Can you share a piece that embodies this intersection?

I have a piece titled “Coral” that I made in 2021. It’s named after the mother in Shay Youngblood’s novel titled Soul Kiss. The protagonist, Coral’s daughter, is a queer Black girl coming of age (and one is always coming of age) immediately post-integration. Her mother is largely absent but she is cared for by her two aunts, elders. I don’t have it anymore–it sold within minutes of posting it online. I have another mixed media piece titled “Miss Celie’s Chair,” which is based off of the character Celie in Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple.” I also have an abstract piece in progress that is made with Nikki Giovanni in mind.

3. What inspired you to create this workshop at The Colored Girls Museum?

Visual art is something we are all seeing all the time–whether it’s on social media, the tags on the sides of buildings, the murals all over Philly, the selfies we take, or obviously, work in museums and galleries, for people who have had access to those spaces. We are all influenced or moved by fifty-eleven pieces of art in any given week, but sometimes it can be difficult to describe what we think about it coherently through language. I study this stuff formally and sometimes I am moved to feeling or thought by something beautiful, or even disturbing, but can’t immediately say why. Poetry is a good way to figure out what you think, to ask a question instead of make an argument. There’s all this gorgeous art in TCGM, so these poetry incubators give us time to think together to figure out what we feel/think/want to say about them. I call it an incubator instead of a workshop because an incubator is where something is made, and a workshop is more teaching. I am doing some teaching, but I’m trying to focus more on the togetherness.

4. How do you envision participants moving between viewing art and creating poetry during the workshop?

We use at least two floors of the three-story museum. First, we will take a look at an example of ekphrasis, which is a poem written by Patricia Smith in her collection titled Unshuttered, about 19th-century photographs of Black people. There is one of two Black women and she’s written about them. Then, we will think out loud about a work of art in the museum, do a fun language exercise, and make a collective poem about that work. Then, a condensed tour of the museum, and participants individually choose a work they’d like to write their own poems about. We play some music and folks write about their selected piece, with help from a few prompts. I’m looking forward to meeting people who have never written a poem, or who have never been to TCGM before. It’s a different poet and different language activities each time I do the incubator. Last time we read a poem by Evie Shockley, and we wrote a collective poem about a painting by Philly-based artist Jazlyn Sabree.

5. As someone who works with both words and images, what does Staged So Black mean to you?

I took that title from a line in the poem by Patricia Smith. I chose to use it as a title because there is the decades-old question: what is Black art? I identify as a Black artist, always. I am not an artist who happens to be Black. I am clear about that. But I am also curious about what “Black” and “art” or “artist” mean together to other people, and what it means for art and artists to announce themselves as Black, so the term “staged” stands out to me. We will be talking about that a little bit this weekend.

6. What do you hope participants take away from experiencing poetry and visual art together in this space?

I hope every participant takes away the idea that there is no one way to make a poem, no one way to analyze a work of art, and that all of us likely have some tools inside ourselves to do these things no matter what we studied or didn’t study. And if they enjoy it, maybe they will tell a friend who will attend the collage making workshop next month, titled Any Day Now. That one won’t include any writing, just visual artmaking.