Are Philadelphians Running Out of Time to Vote?

Low voter turnout could be a result of time poverty, experts say.

Kiara Sabur is a Philly Gen Zer who’s currently not registered to vote – and not for the reasons some might quickly assume.

“I’ve just never had the time,” Sabur, 26, explains.

Her exhaustive work schedule as a baker is one major factor.

At 5 AM every weekday morning, Sabur leaves the home she shares with her father for her job at 12th Street Catering. If it ran regularly, Sabur would be getting on the 7 bus to get to her job.

Instead, she walks about an hour from her home in Point Breeze to 33rd and Spring Garden for her 6:30 AM shift. She puts on her chef jacket and non-slip shoes and gets to work prepping for the day.

She spends her shift on her feet, scooping cookie dough, making sure her measurements are precise, and watching the oven. Around 2:30 PM, it’s time for her to go home. Because the 7 also runs irregularly in the afternoon, Sabur will often choose to walk home. On average, Sabur will spend 10 hours on her feet everyday.

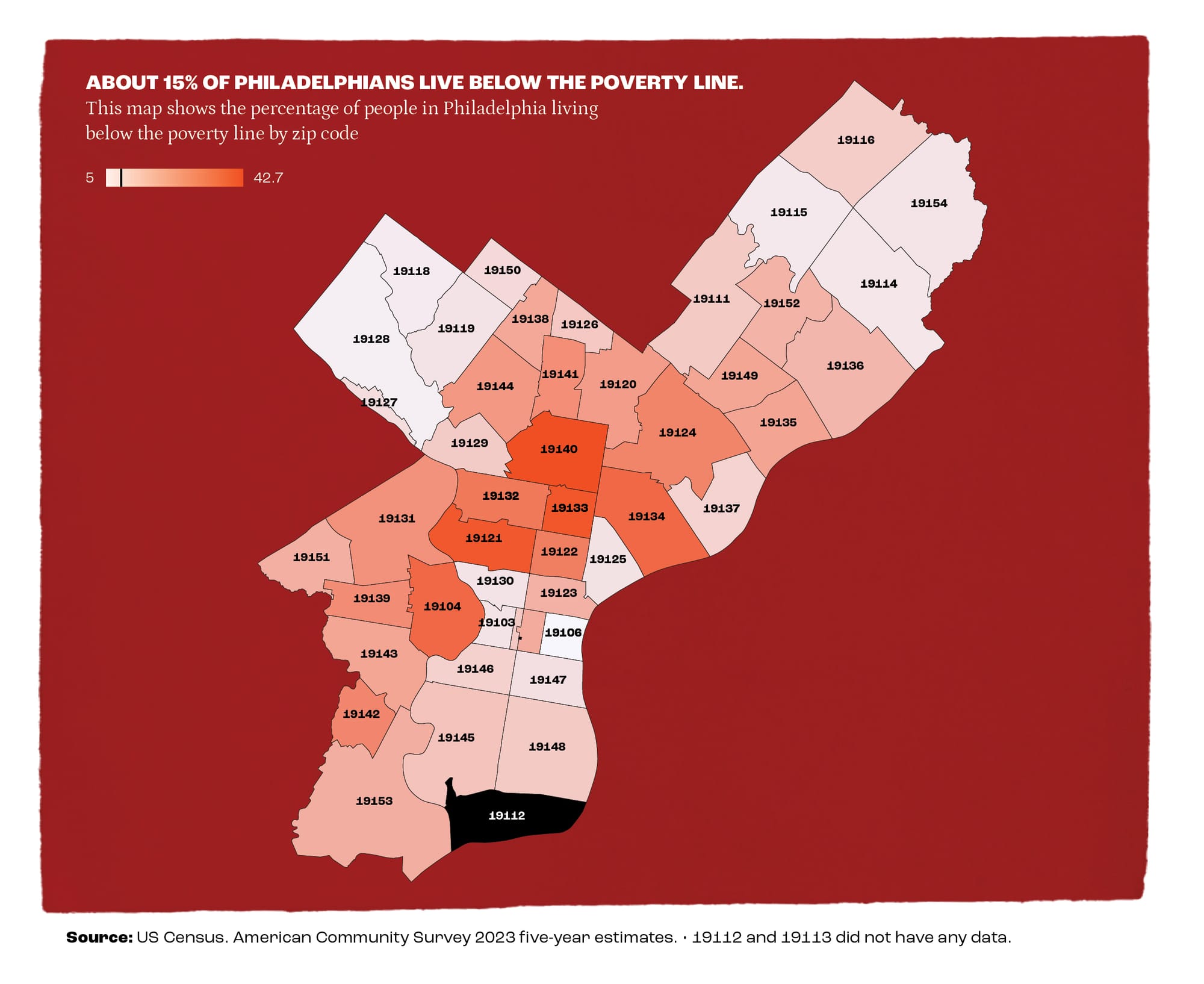

Sabur’s socioeconomic barrier to voter registration is more common in Philly than socially considered.

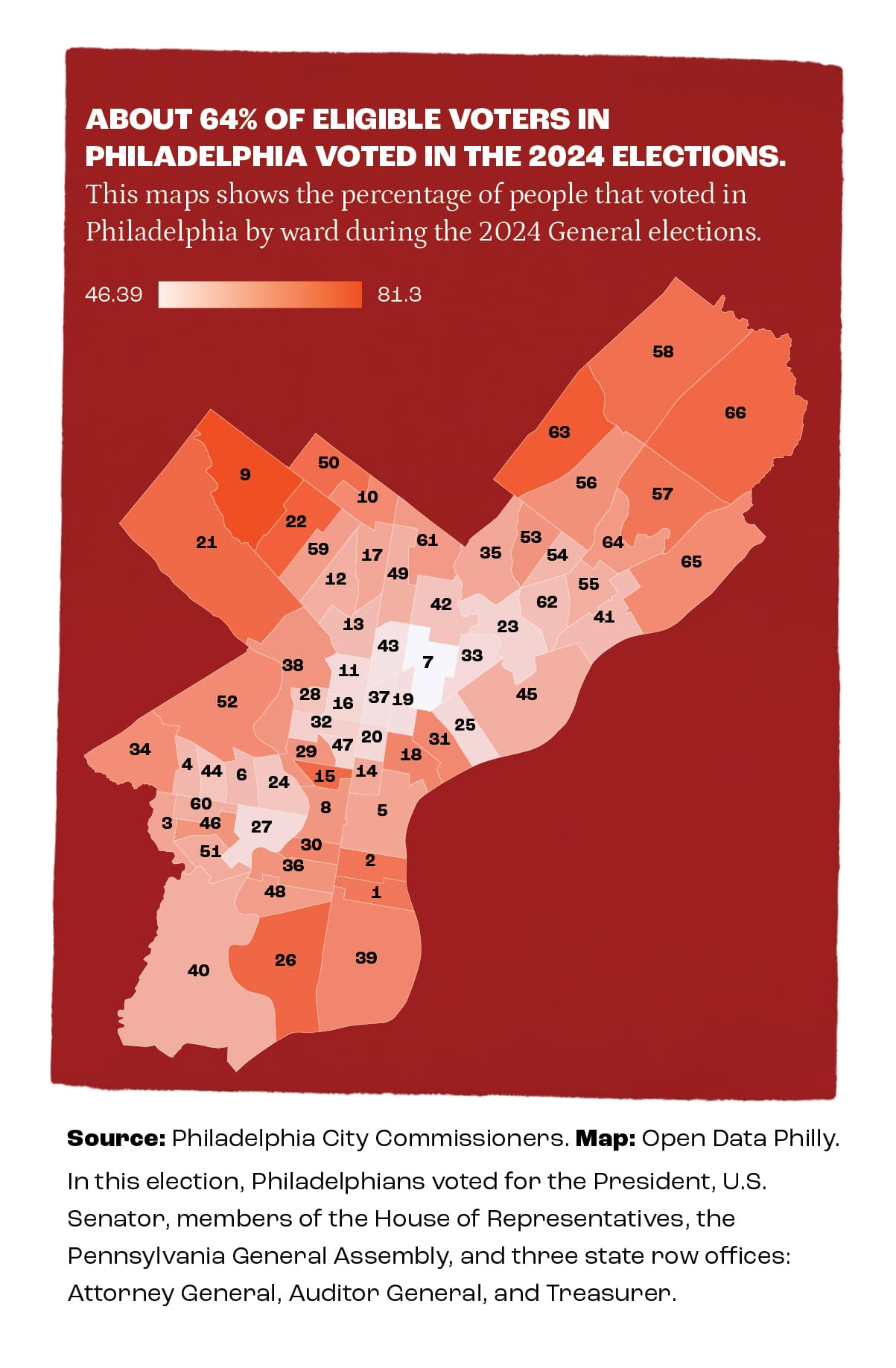

According to Pew’s 2025 State of the City report, the majority of Philadelphians are food preparation workers, cashiers, janitors, home health aide workers, and construction laborers. All of which typically work outside of a 9-to-5 shift. With looming SEPTA cuts from a lack of state funding, in a state where there is no mandated voter leave, Philadelphia’s low voter-turnout problem could intensify with limited public transportation or no service at all.

Experts say that Philadelphia's most vulnerable populations could simply be running out of time.

“That scarcity of free time really affects your ability to do things like research candidates, go to candidate forums, register to vote, and be able to stand in line at polling places,” Rasheedah Phillips, director of Housing at PolicyLink, told The Philly Download. “I have typically worked jobs that give you the day off to go vote. That’s a privilege that not every job provides. That then becomes a form of voter suppression.”

Phillips’ book, Dismantling the Master’s Clock on Race, Space, and Time, examines the idea of time poverty, which is when people don't have the time to do tasks that are essential to their survival and/or improve their quality of life.

“I saw this a lot when I was an attorney in Philadelphia. I’ve had tenant clients who were late to court because of a SEPTA strike, something that is out of their control, and got evicted as a result because they had no alternative to get to court,” said Phillips. Lower income people and people of color are more likely to experience time poverty, experts say.

Margaret Greene, senior fellow at Iris Group International and author of the 2020 study "Time poverty: Obstacle to women's human rights, health and sustainable development", explained further in an email: “Time poverty, while usually framed as a gender issue, can also intersect with race. Race can deepen time poverty by shaping what kinds of work, commuting, caregiving, and systemic barriers people face — making some groups systematically more ‘time poor’ than others.”

“Things like occupational segregation (concentration in low-wage or precarious jobs), commuting challenges, unequal care in the household, administrative burdens of interacting with institutions, and other factors can all contribute to time poverty,” Greene wrote.

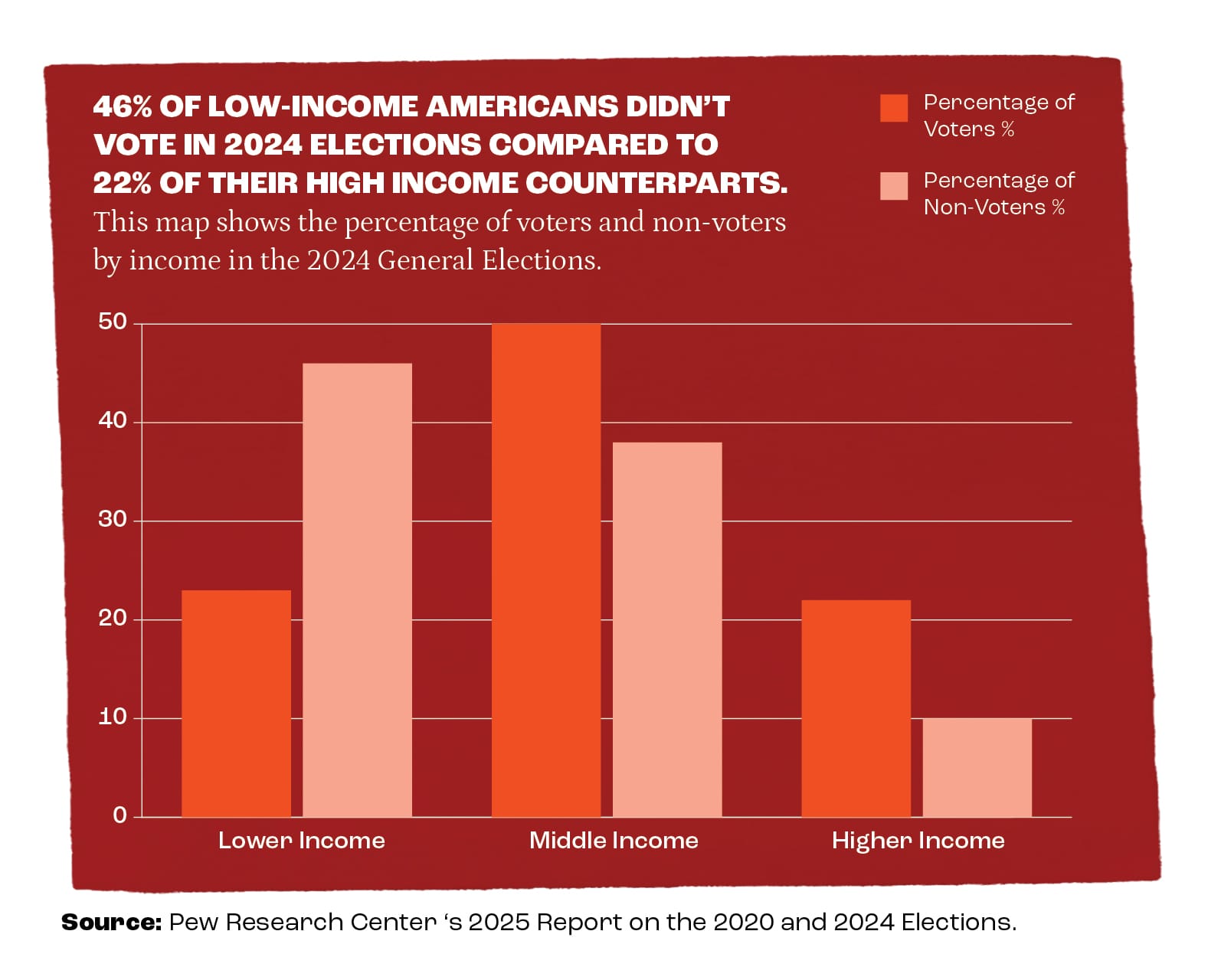

Earlier this year, Pew Research Center released a report on voter turnout from 2020-2024. In 2024, 46% of low-income eligible voters didn’t vote, which is down from 50% in 2020. Twenty-seven percent of people named scheduling conflicts as the reason they didn’t vote in a 2022 US Census survey on the Midterm Elections.

So why do low-income people vote less than their wealthier counterparts? Because low income people have less time to engage, experts say. The responsibility of time investment should fall on the candidates, Antonio Ingram, senior counsel on the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Educational Fund and Harvard Racial Justice Fellow, explained. Ingram believes that candidates could spend more time engaging the communities they serve.

Candidates “need to stay invested in their communities year round, not just when they need their ballot,” said Ingram, “because then you do know what their needs are and you can have credibility.”

Ingram also noted that a lack of education on the political process may impact voter turnout. April Ashe, the executive director of the Pennsylvania Legislative Black Caucus, agreed that candidates should be more direct about how long it takes for campaign promises to become law.

“Be a candidate of your word,” said Ashe, “Don’t tell [voters] that you’re going to get them minimum wage or healthcare access when you don’t know the group project that is the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. We had a bill that took us 14 years to get 3 lines of legislation in.”

Other factors beyond time scarcity certainly impact voter turnout. In the 2020 Poor People’s campaign report, 24% of low income voters also claimed that they didn’t like the candidates and their issues or they felt like their vote wouldn’t matter.

In another Pew survey, 33% of Americans believe that members of Congress do a good job at promoting laws and policies that serve the public interest, some of the time. Ingram believes candidates often don’t understand their own ability to impact everyday people’s lives.

“We have candidates that underestimate their ability to influence things,” Ingram said, “If you have a scenario where an elected official can help advocate to ensure that you only pay $35 for a life saving drug like insulin. That can impact people’s aunties, moms, dads. That is one way candidates can impact people’s lives in a tangible way.”

Ashe also pointed to a lack of polling places as an obstacle to voting. She thinks that if more people were willing to work polling places, there would be more open.

When asked about the responsibility of making the infrastructure around voting better, Rasheedah Phillips said that it is a communal issue.

“I think ideally, the responsibility to make right and repair these systems should not be on us [marginalized communities],” said Phillips, “But I think the reality is that if we want something, we have to build it ourselves. We can’t ever just rely on what we think we’re owed because it’s not going to get us where we need to be.”

Phillips noted the ways in which voting accessibility has changed over the years to help more disadvantaged voters fulfill their civic duties, like early voting, absentee voting, and mail-in ballots. But she also highlighted that even though voting was a tough right to secure for the Black community, she understands the range of emotions that come with voting.

“But I think people have justified critiques of these things [voting],” said Phillips, “if we’re talking about truly liberated people, people have the choice. And if they don’t make that connection or don’t want to make that connection with democracy, politics, and who's in power. That’s okay too.”