“Rewriting Philadelphia: 20 Years of Literacy, Power, and Possibility”

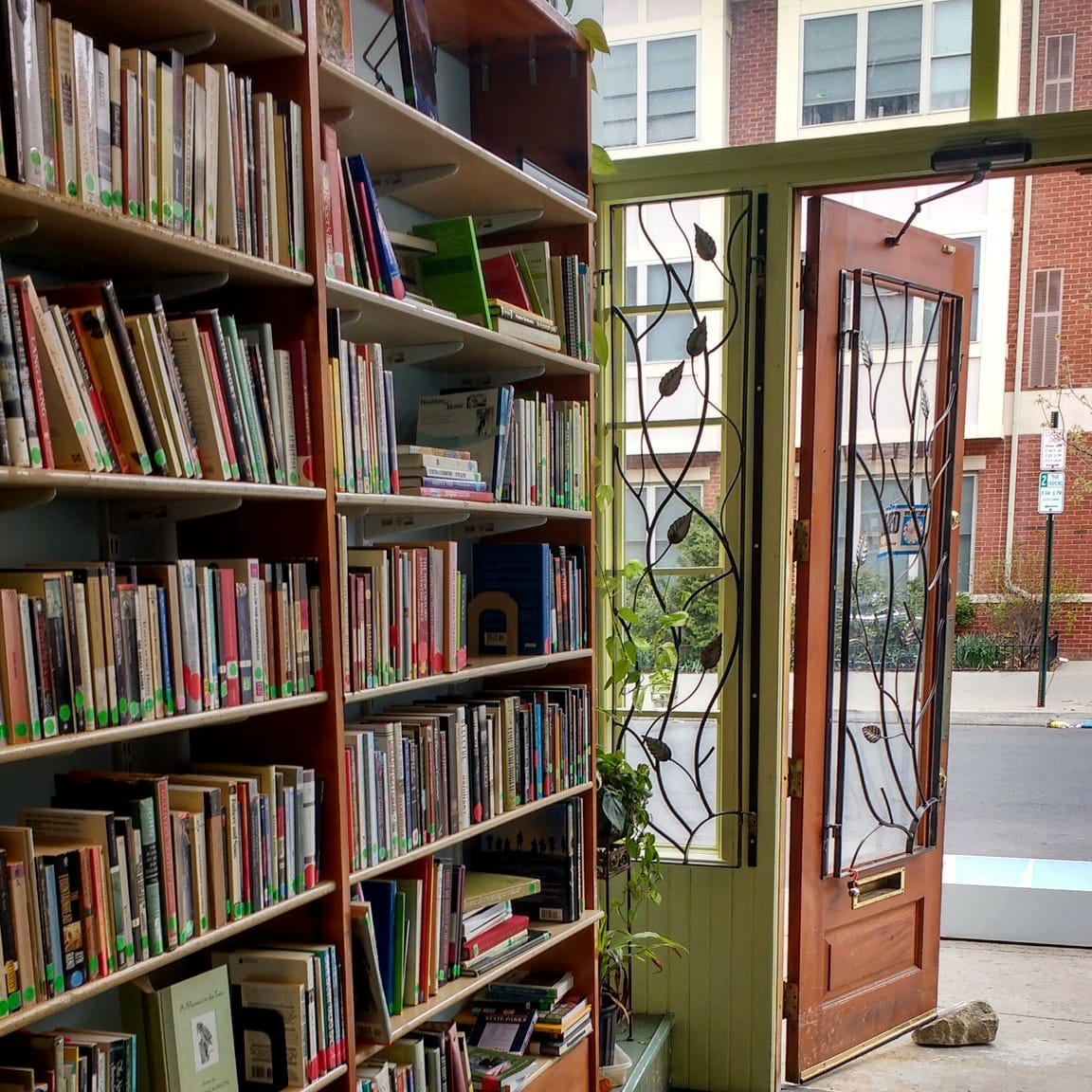

For twenty years, Tree House Books has stood as a quiet revolution on Susquehanna Avenue. What began as a neighborhood reading room has become one of Philadelphia’s most trusted literacy incubators. Proof that a single story can spark a movement.

The organization’s recent 20th anniversary honored journalist Tamela Edwards, author and educator Dr. Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, and Laurie Smith, Chair of the Board at Tree House Books. Also recognized was Senator Sharif Street, whose recent $98,048 contribution will help expand book-access programs across the city.

But the celebration itself was only a moment. The deeper story lives in the ongoing question: How do we, as a city, ensure that every child can read, imagine, and own their story?

I spoke one-on-one with these four leaders to understand what Philadelphia has learned about literacy in the past twenty years and what must come next.

When I met with Dr. Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, she didn’t start by talking about books or classrooms. She started with a voice.

“Literacy isn’t only the ability to read. It’s the power to name your world. When young people learn that their words have weight, they begin to imagine differently and that’s the beginning of freedom.”

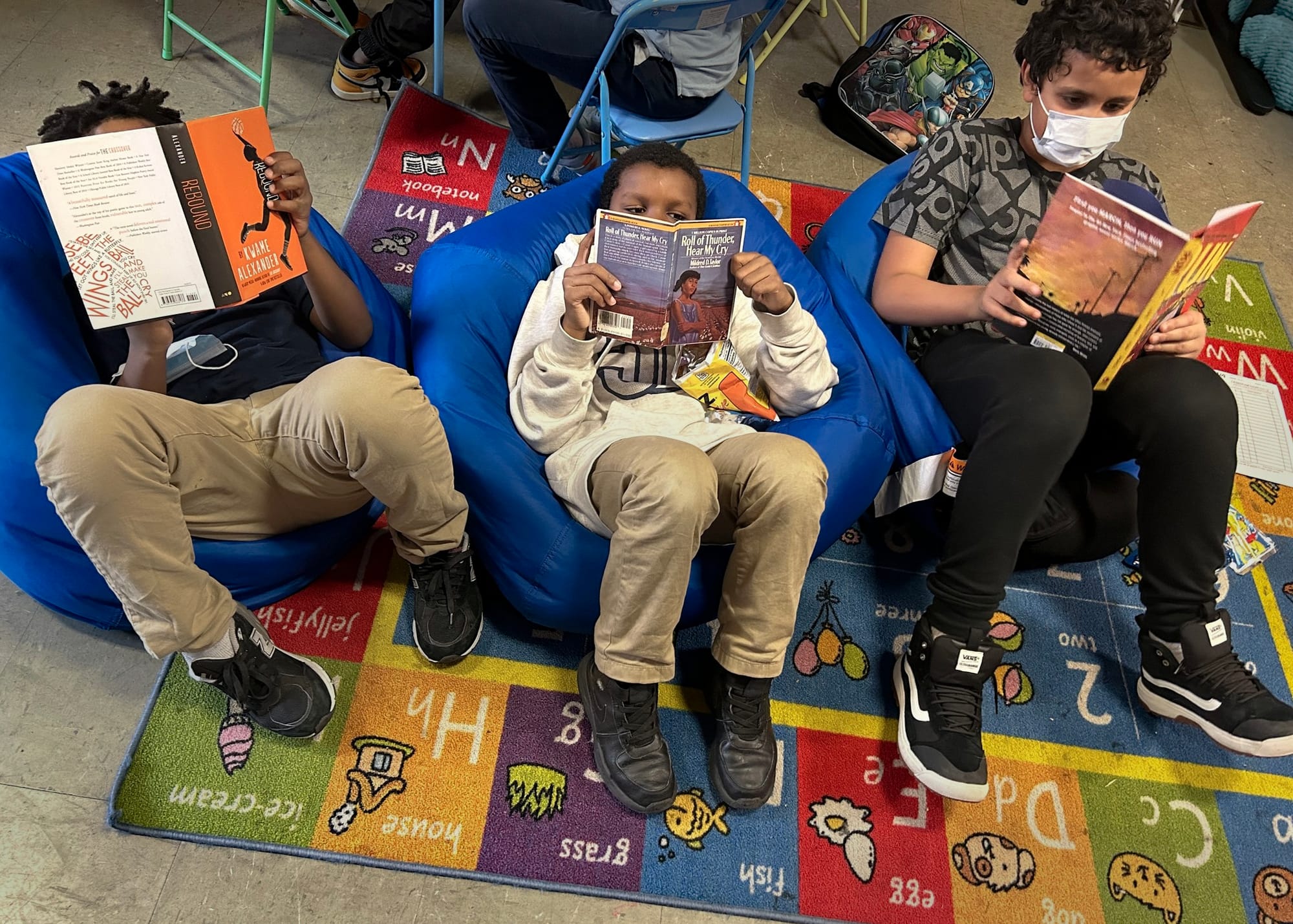

Sullivan’s relationship with Tree House began two decades ago while she was a graduate student at Temple University. Alongside Dr. Eli Goldblatt and Natasha Leonard, she helped launch writing workshops for neighborhood youth sessions that would lay the foundation for Tree House’s literacy model.

“We’d sit around a small table. Ten kids, a few notebooks, a stack of donated books and you could feel transformation happening. A child would write one line about their block or their grandmother, and suddenly they were awake to their own voice. That spark? That’s what literacy does.”

For Dr. Sullivan, the challenge now is sustaining that spark beyond moments of inspiration.

“Philadelphia has brilliant programs. Tree House, libraries, after-school collectives; but they shouldn’t be running on exhaustion and hope. If we’re serious about literacy, we have to fund it like we fund public safety. Because literacy is public safety.”

She believes the future depends on reimagining where reading happens.

“Books shouldn’t live only in classrooms or libraries. They should live in barbershops, in rec centers, in corner stores. Every neighborhood space can become a literacy space if we see it that way.”

As both a journalist and a mother, Tamala Edwards views literacy as personal. To her, reading is more than academic progress, it’s identity work.

“Every book a child opens is a mirror and a window. It’s how they see themselves clearly and how they see beyond what’s familiar.”

Edwards is deeply invested in dismantling what she calls “the fatigue of forced literacy”. The idea that reading should feel like a chore.

“We’ve turned reading into something transactional. We measure it, grade it, test it; but rarely do we let children fall in love with it. We need to make reading emotional again.”

Representation, she added, is essential to that love.

“When a child from North Philly opens a book and sees someone who talks like them, looks like them, feels like them, that’s not just representation, it’s validation. It tells them: you matter, and so does your story.”

Edwards imagines a future where reading is as natural as rhythm.

“If we can make literacy feel the way music does in our city; something that moves through every block, every home, every voice, then we’ve truly transformed the culture.”

For Senator Sharif Street, the issue of literacy is inseparable from equity. He sees reading not only as an educational right but as a structural necessity.

“If a child can’t read, they’re locked out of opportunity. That’s not an educational failure, it’s a systemic one. Literacy is the foundation of justice, employment, and civic power.”

Street’s recent $98,048 donation to Tree House Books is part of a broader push to embed literacy funding into Pennsylvania’s long-term community development plans.

“We can’t keep treating literacy as a side project. It belongs in every policy conversation; housing, healthcare, criminal justice. Every outcome we care about traces back to whether or not a child can read.”

He spoke passionately about bridging the gap between grassroots action and government responsibility.

“Tree House has done something remarkable: it’s created proof. Now our job as policymakers is to scale that proof. We have to make what’s working in one corner of the city accessible in every zip code. The day every Philadelphia child has access to a book that reflects them, that’s the day we begin to balance the scales.”

Laurie Smith, who chairs the Tree House Books board, sees the organization’s twenty-year journey as both a celebration and a challenge.

“When we started, we asked, ‘Can we even do this here? Now we know we can. The question is, will we make it permanent?”

Smith spoke candidly about the conditions that often make reading secondary in families’ lives.

“When parents are working two jobs, when rent is rising, when libraries are underfunded, books fall to the bottom of the list. That’s not disinterest. That’s survival. Our job is to bridge that gap.”

For her, the next phase of literacy work in Philadelphia must combine resources with empathy.

“We’ve built the blueprint. Now we need policy, partnership, and persistence to scale it. Every child deserves the dignity of reading in a space that affirms them. If a child doesn’t have a book, hand them one. If they don’t love reading yet, read with them. That’s how movements start. One connection at a time.”

Tree House Books may have reached its 20-year milestone, but the story of literacy in Philadelphia is still being written. Each voice I spoke with returned to the same central idea: literacy is not a privilege. It is survival, creativity, and agency wrapped in pages.

Dr. Sullivan called it freedom in real time. Tamala Edwards described it as a mirror and a bridge. Senator Street called it justice work. Laurie Smith called it proof of possibility. Together, their words form a collective blueprint for the city’s next twenty years of literacy. One built on access, representation, and joy.

Philadelphia has always been a city of storytellers. The challenge now is ensuring that every resident, from child to elder, has the tools to write their own.

“The beauty of literacy,” Dr. Sullivan told me, “is that it never ends. There’s always another story waiting to be told. Our task is to make sure everyone gets the chance to tell it.”