Rasheed Ajamu Is Rewriting the Narrative of Germantown—One Post, One Story, One Neighbor at a Time

If you want to understand what’s happening in Germantown—not just what’s being built or debated, but what’s being remembered, grieved, celebrated, and imagined—you talk to Rasheed Ajamu.

If you want to understand what’s happening in Germantown—not just what’s being built or debated, but what’s being remembered, grieved, celebrated, and imagined—you talk to Rasheed Ajamu.

A Germantown native, Ajamu is the editor of the Germantown Info Hub, a community-powered journalism project under Resolve Philly. But "editor" doesn’t quite capture the scope of what they do. On any given day, Ajamu might be coordinating interviews with neighborhood elders, fact-checking a piece on a zoning meeting, facilitating a civic storytelling event, and posting a meme that breaks down local politics with a dose of humor and clarity. “Organizing is storytelling,” Ajamu says. “It’s about helping people see each other, imagine something different, believe in the possibility of change.”

That ethos powers everything Ajamu does—from writing and editing to digital curation and public engagement. Their approach to journalism is hyperlocal, yes, but it’s also deeply human. In a time when newsrooms often treat communities like Germantown as sites of crisis or charity, Ajamu insists on depth, dignity, and context.

“We deserve archives that tell the truth and don’t rely on us to be perfect,” they say. “I care deeply about Black people, about joy, about nuance. I’m trying to live honestly—and I think in Stories.”

Known online as phreedomjawn and dagtowngem, Ajamu has cultivated a growing digital presence that merges mutual aid organizing, queer and trans liberation work, and local political analysis. Their Instagram feed is a timeline of care: carousel posts on neighborhood history, fundraisers for neighbors in need, Black prom photos, reminders to rest, and sharp political commentary—all filtered through a distinctly Philly voice.

It’s part public service, part cultural preservation, and part refusal. A refusal to let Germantown —and Black Germantowners in particular—be flattened by external narratives or forgotten in broader city discourse.

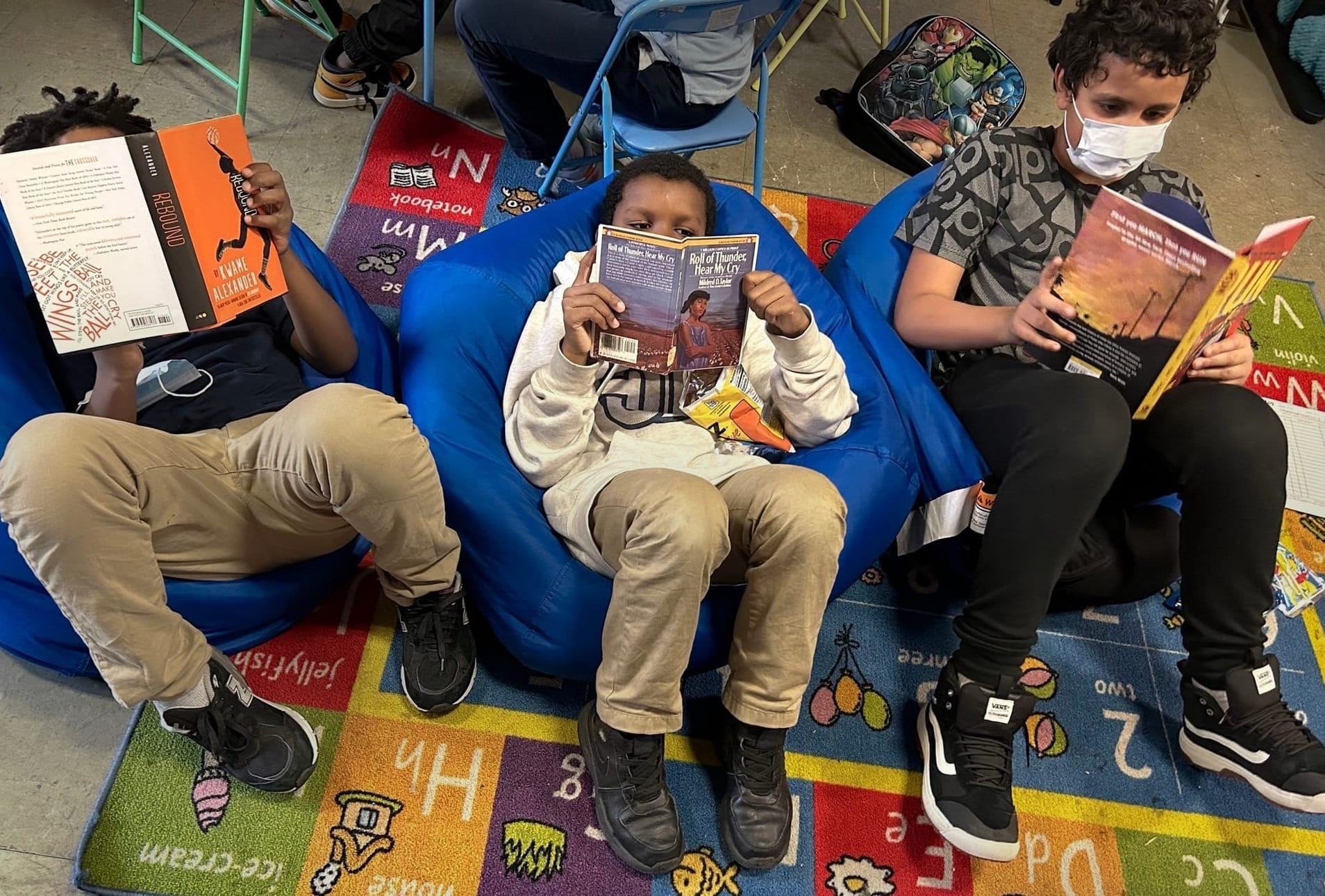

At the Info Hub, Ajamu leads a mighty team committed to “meeting the information needs of Germantown residents with care, accuracy, and accessibility.” That often means publishing stories that traditional outlets overlook: the return of the neighborhood’s iconic Tin Man statue, the importance of Black prom culture, local town halls, housing initiatives, and mutual aid efforts.

“We’re not just reporting on Germantown. We’re of it,” Ajamu explains. “This is about documenting the people, the memories, the transformations in real time. What does it mean to leave behind stories that help us remember who we are?”

This sense of place, of rootedness, sets Ajamu’s work apart. They don’t treat Germantown as a beat—they treat it as home. That closeness invites a different kind of journalism: slower, more relational, deeply invested in consent and collaboration.

Their inclusion in Mural Arts Philadelphia’s We Did That mural in 2023—a tribute to Black and Brown Philadelphians shaping the city—was a public acknowledgment of their quiet, persistent labor. “It was surreal,” Ajamu says. “But it also reminded me of the responsibility. That we’re not just experiencing change—we’re narrating it. Shaping it.”

That shaping matters now more than ever. Germantown, like so many historically Black neighborhoods, is facing the overlapping forces of gentrification, economic precarity, and civic neglect. In that context, journalism becomes more than a tool for information—it becomes a strategy for resistance, recovery, and imagination.

Ajamu doesn’t pretend to have all the answers. In fact, they’re refreshingly transparent about the learning curve. “I’m learning in public most of the time,” they admit. “But I try to lead with care. With curiosity. And with the belief that people deserve to be seen.”

That people-first approach shows up in their process. Whether they’re reporting on a neighborhood protest or hosting a community conversation on police funding, Ajamu prioritizes consent, clarity, and context. “If someone ever asks me to take something down, I do. No questions asked. The story isn’t more important than the person.”

It’s a stance that runs counter to much of the digital media landscape, where virality often trumps vulnerability. But for Ajamu, documentation is sacred work. “I think about legacy. I think about how often Black folks’ images and stories have been used without our permission. If I’m contributing to an archive, I want it to be one people feel proud of. One they feel seen in.”

Lately, Ajamu has been working on a new photo-and-interview series focused on Black elders in Germantown. The goal is simple but urgent: to preserve their voices, their wisdom, their style. “They’ve seen so much. Survived so much. And I think we overlook them too often in our movements,” they say. “This is my way of honoring them.”

Still, Ajamu is the first to remind you that storytelling isn’t always about the public. Some of the most radical work, they argue, happens behind closed doors: in private reflection, in small gatherings, in choosing rest over constant production. “Sometimes the most radical thing is just surviving with your joy intact,” they say. “Taking a walk and not posting about it. Making something just for yourself. That’s where a lot of my healing lives.”

When asked what they hope people feel when they encounter their work, Ajamu doesn’t hesitate: “Seen. Loved. Like they matter. Even if just for a moment.” That moment, in Rasheed Ajamu’s world, is where transformation begins.