Hurricane Katrina, 20 Years Later: Pulitzer Prize winner Clarence Williams looks back

Williams, a West Philly native and longtime photojournalist, is showcasing his work at InLiquids' newest exhibit, “Revelations: An Evolution of Introspection.”

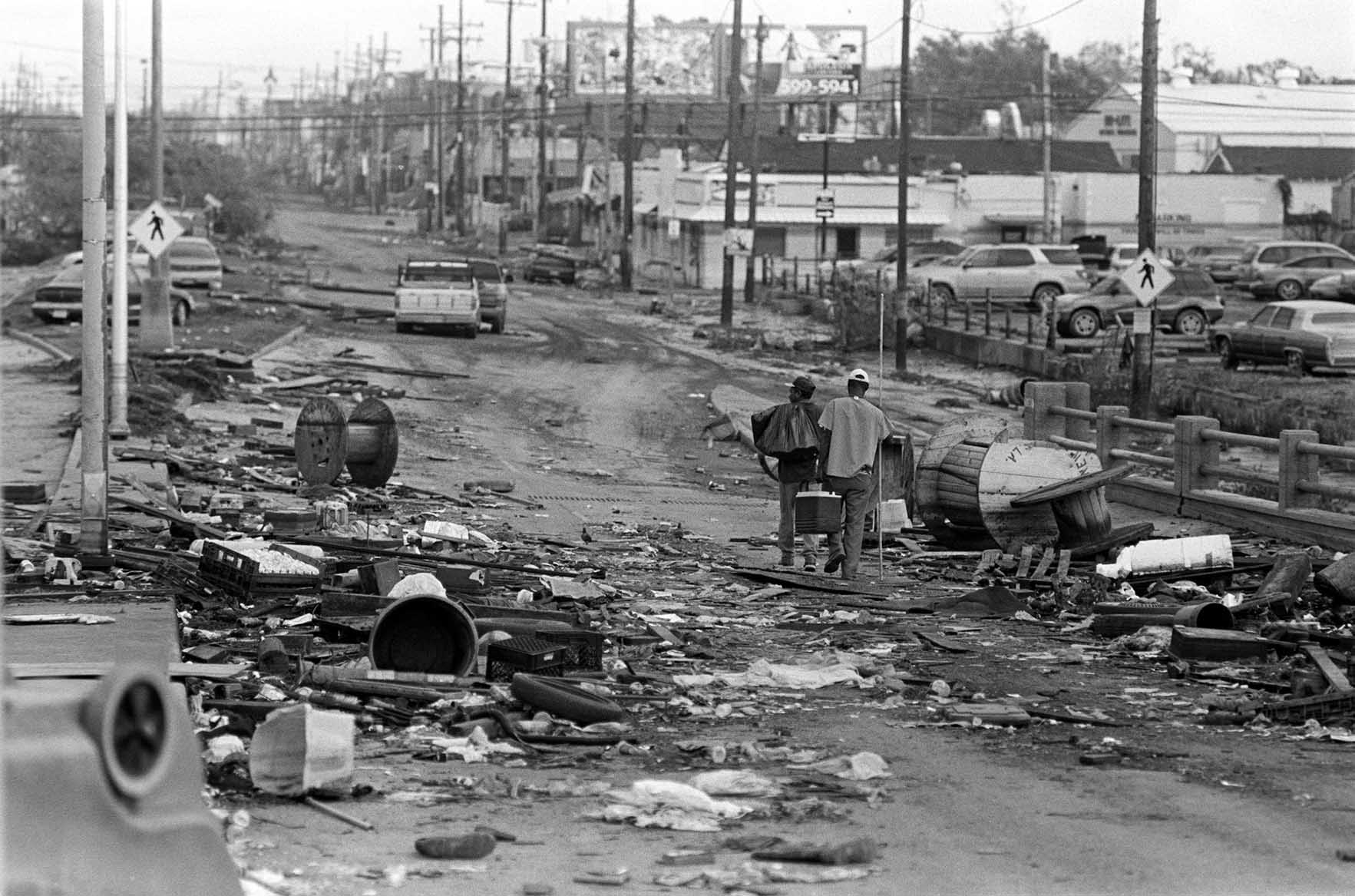

During Hurricane Katrina’s mass destruction in New Orleans, Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist and West Philadelphia native Clarence Williams took refuge with his family in their home attic for four days. Eventually, they climbed onto their roof for another three days as water engulfed their city blocks and whole communities.

After a helicopter successfully rescued them, Williams promptly returned to New Orleans once the water levels lowered. Equipped with a goal and his camera, Williams embarked on a mission to capture New Orleans life in its sharp contrasts, as seen in the remnants of homes and collective resilience.

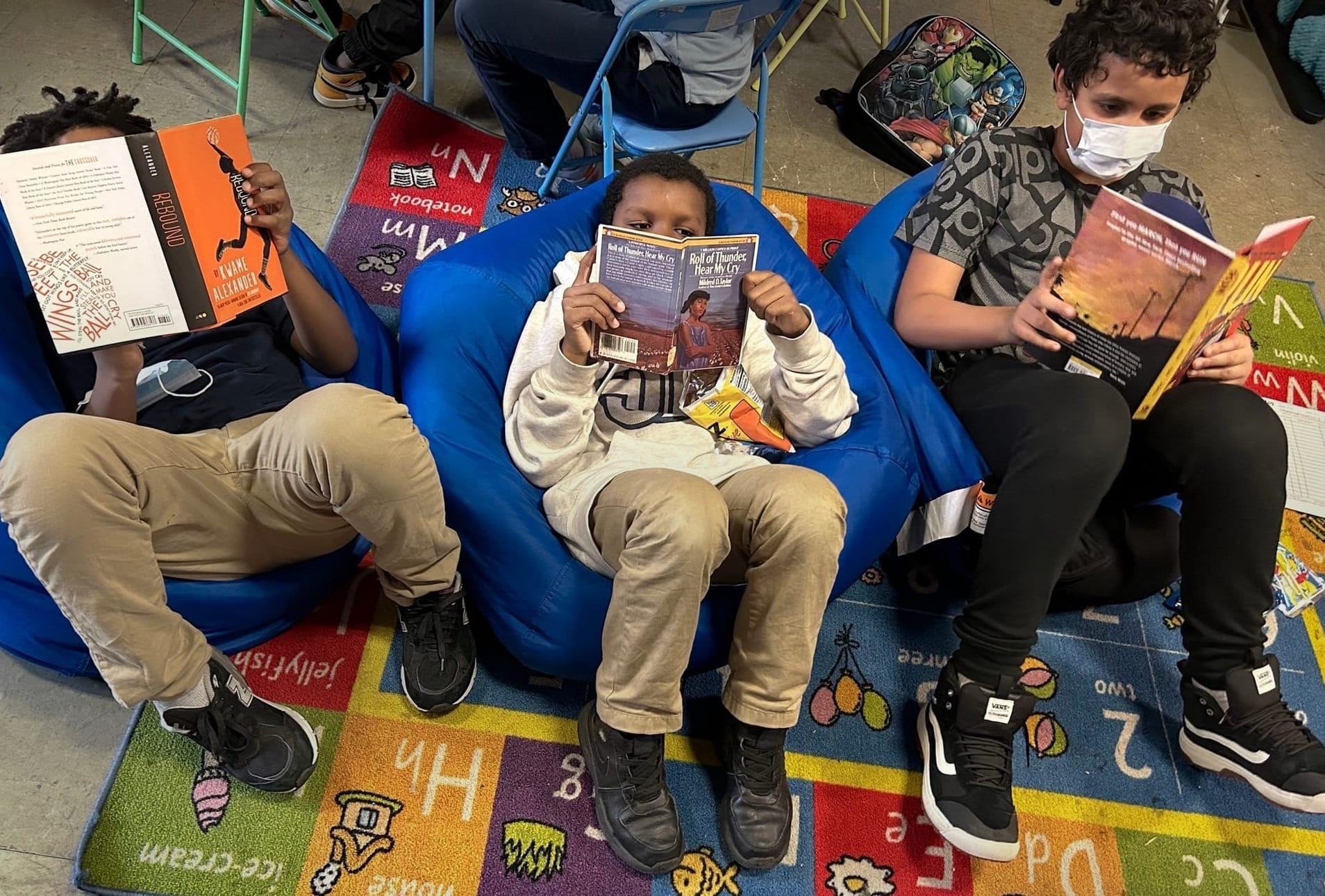

This year marks 20 years since the horrors of Hurricane Katrina. Williams, alongside poet and longtime collaborator Philly native Ursula Rucker and Philly-based photographer Donald Camp, are showcasing their work at InLiquids' newest exhibit, “Revelations: An Evolution of Introspection.” This exhibit aims to explore the intersections of climate change and Black livelihood and how we can learn from our peers who have persevered.

Williams spoke with The Philly Download to recount his career in New Orleans, what he endured before, during and after Katrina, and what memories cling to him after 20 years. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Editor’s Note: This interview includes descriptions of disturbing language and violence that Williams witnessed in New Orleans and Palestine, among other places. We believe it’s important to share Williams’ experience, but be forewarned that some details may be triggering.

Favorite memories and places in Philadelphia?

Williams: I definitely love the zoo. It’s great. I used to go to the zoo a lot with my dad and mom. Sledding at Clark Park in West Philly. I don't know if they still do it, but they used to have a free Friday joint at the [Philadelphia] Art Museum.

I have three distinct Philadelphias: There was Philly from birth through 18. There was this little brief period of time I came back to Temple, which I shall not be discussing. Then, there was this third time, when I came back to Temple and started taking pictures. The really wild thing is, I haven't been back to Philly in 15 years. It’s been a long time.

Is this going to be a homecoming for you? Are you excited?

Williams: Yes — and uncomfortable. Just this morning, I was thinking to myself, ‘I don't want to go. I should cancel this sh**.’ (Laughter.)

Favorite Things About New Orleans?

Williams: The typical sh** that everybody says: the culture, the music… .

I don't mind the humidity. I'm always okay with it, even though I'm having an air conditioning issue in my house right now. That's a whole different thing. And my family— I have a very big family here. I spent my summers here as a kid.

What calls you to photography?

Williams: I really wish it was this beautiful, sexy story. It's so not– it’s so ridiculous. I remember once in high school, I had the idea that I wanted to be a photographer. So my parents bought me a camera. We got robbed. They stole only my stuff. After my camera was stolen, that idea was gone. Fast forward to college, I did my first year at USC, second year at Morgan State, Temple my junior year, dropped out. [There was] a period of time aspiring to be a poet after dropping out of school in California, then Temple again.

I left Philly at 18, and my parents moved to New Jersey. I was dejected. I lost all my money in LA. I go back to the Temple and I'm living in New Jersey. I was just like, ‘What more could happen to a brother? This is terrible.’ Temple used to have these course catalogs back in the day, and I'm like, ‘You know what? I don't give a f*** what it is. Whichever has the shortest amount of requirements for me to graduate with all that I've done already, that's gonna be my matrix. I just gotta get the f*** up out of here.’

Journalism. Nice. I thought it was going to get me out of this situation quickly. Lo and behold, my first class was basic photography. I was loving what was going on, but I didn’t understand what was going on. To this day, I have never fallen so hard in love with a person, a thing, or a mission as I did with this.

What memories cling to you during the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina?

Williams: It was very quiet in the house. I remember there were a couple of things that I saw that were horrifying. I remember once, my friend and I were out taking pictures when we got back [to New Orleans]. We were watching the dogs eat a body.

I'm so proud to be from Philly, very proud. But there was a moment when New Orleans became my home. I remember that specific moment when the city was, for the most part, empty except for folks who were working— military, police, a couple of volunteers… lots of journalists. There was one open bar, and these two white guys I was sitting next to, but I wasn't with them.

I remember I was listening to their conversation, and this white boy said, ‘New Orleans is so much better now that all the n***** are gone.’

I didn’t have a lot of means, but I did have a little means… I was working unattached [to a company.] I was no longer associated with the LA Times at this point in my journey. I whispered to myself, ‘I guess I've got to move here.’ I didn’t leave. That was the reason why.

Do you consider yourself and other survivors of Katrina to be “refugees”?

Williams: Well, truth be told, if it wasn't for this commemoration, people don't really talk about Katrina a lot. I noticed that. People talk about it five years later, 10 years later… American mass media loves anniversaries. It’s packaged and it works. But in between those remembrances, no one talks about it.

There’s a tragedy every day. We don’t talk about Hurricane Katrina, but we don't talk about slavery. I consider [survivors of Katrina] to be Internally Displaced People. IDPs. We're not refugees; we're from this country. We built this motherf*****. How are you gonna call us refugees?

To this day, I find that being called a refugee is very insulting. I don't think it's ever gonna be repaired.

How have you maintained purpose and a mission after the trauma of Katrina?

Williams: I've been through a lot of terrible things as a photojournalist. I’ve been to mass graves in Kosovo and I have walked through landmines in Angola. I have been in Hebron, where I've caused the death of a child.

The Israeli Defense Forces were shooting rubber bullets at these kids who were throwing rocks at them and I was hiding, taking pictures. Then I came out, and I had “Press” emblazoned across my back to take some more pictures. Then, as I came out, there was this silence. Once they started shooting again, it was not rubber bullets. They were live rounds. The kid that I was photographing took a bullet right in the head. I know they were trying to shoot me, but they shot him.

All this is to say, there has been this life as a photojournalist that I have been through that prepared me for Hurricane Katrina. When I think about it, Hurricane Katrina was my last project. That was it. I haven't, really, done anything like that since.

I have no choice but to continue spreading the idea, spreading love and living a love ethic, due to everything I have been through. My path was to study the way I studied, work the way I work, to get to my way of telling stories.