From Takeout to Testimony: The Black Dragon’s Recipe for Communal Solidarity

It’s an almost impossible task within the Black Community to find a soul who has not been touched by the power of Orange Chicken or Combination Rice.

It’s an almost impossible task within the Black Community to find a soul who has not been touched by the power of Orange Chicken or Combination Rice. The ever-present nature of the local Chinese takeout restaurant represents an integral part of Americana– intercommunal relationship between the Black and Asian communities that dates back to the 20th Century.

Even as discriminatory laws from the century prior, like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, ostracized Asian immigrants from fully partaking in “American” society, exclusion was also a tale too often understood by African Americans. In Black communities, the embers of solidarity sparked fires that would sizzle for generations, from kitchen woks and cast iron skillets to entire civil rights movements.

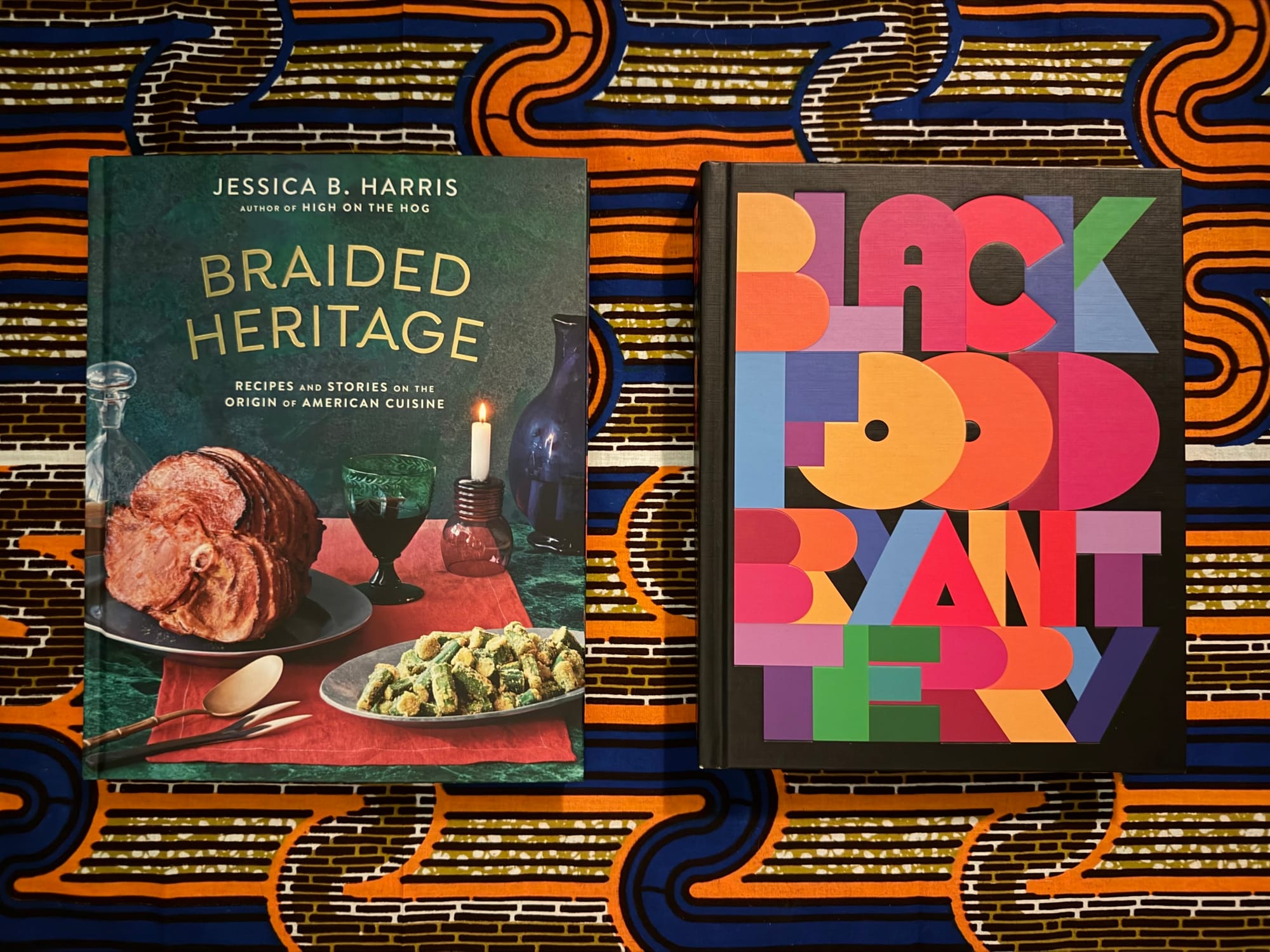

In Philadelphia, The Black Dragon– a Soul Food and Chinese-infused establishment owned and operated by Chef Kurt Evans, is a true testament to that solidarity and collaboration. At The Black Dragon, Egg Rolls hold not only collard greens, mac and cheese, and BBQ chicken, with a dollop of General Roscoe sauce for kick– but heritage.

A proud Philly native, Chef Evans rooted his creative vision on the corner of Rodman Street, taking over the Chinese restaurant that already existed. In the heart of West Philly– the very location– and subsequent rebirth under Black ownership is a silent, yet powerful testimony to ANYONE who would dare to challenge the cultural legitimacy of this community.

In a society that far too often fails to understand the nuances of Chinese American food and the impact that the Black community had in shaping it, Chef Evans is crafting cohesion and community, one order at a time.

As The Black Dragon nears its first anniversary, I spoke with Chef Evans about his overall mission, discussed the historical significance of the Black and Asian communities’ bond, and the importance of organization for any marginalized group seeking empowerment.

Joi Weathers (JW): “Thank you so much for taking the time to sit and chat with me especially seeing it’s been a rainy mess on and off again for the past couple of days. So jumping right into it, what does The Black Dragon represent to you, and why do you feel your mission matters?"

Kurt Evans (KE): “No problem at all. I’m happy to sit down and talk about the restaurant. You know it came about because my mentor Earl Boyd, founding chair of the West Philadelphia Financial Services Institution, informed me that money was being lent to support minority businesses and that a lot of Chinese American stores were closing, so there was inventory to choose from. I was a young ambitious cook, and I always felt food was a connector, and that I could tell stories with food, and share experiences. So, it has always been important to me to make this central to my business and for the community.”

Chef Evans’s focus on community is evident, from his emphasis on Black mentorship to painstakingly researching his demographic so he can authentically serve them. Even the physical structure of Black Dragon signals inclusivity and dignity for the community it inhabits. Community is at the core of his success.

JW: “You’re coming up on a year of being an establishment. What lessons have you learned that carry over into your activism and being a safe space for Philly residents?”

KE: “Well, when you look at stores in urban areas, they’re sometimes sectioned off with plexiglass, or not accessible. So, I made sure when we were remodeling, there was the opportunity to have accessible bathrooms, removing the glass from the front counter. Even though it’s not the largest space, giving people the option to sit down and eat their food. Basically, treating people with respect and dignity, not presuming or worrying about being robbed. I wanted to make sure people felt wanted here.”

But it shouldn’t be assumed that Chef Evans just remodeled a Chinese Food restaurant. He curated a space that gives Blackness a different way to perceive communal connection.

JW: “Some might look at the historical relationship between the Asian and African American communities as transactional, dependent on services, and not necessarily a true connection. Do you feel this is a fair assessment of these communities?”

KE: “During my research I found out the foundation of Chinese American takeout was based on the Black community. We’re a reflection of their first customers and catering to American fare. For instance, Egg Foo Young isn’t traditional Chinese cuisine. Rather, it’s the culmination of realizing Americans loved omelettes and gravy, so it became a menu staple. In the beginning, there was camaraderie. We can look to the 50s-70s. We lived together in our neighborhoods. If anything, White Supremacy shifted solidarity in the sense, providing business opportunities to the Asian community, pulling into the “good immigrant trope,” while still outcasting the Black community from the same advantages. But, it’s always important not to blanket the entire Asian community.”

While Chef Evans didn’t have a homogenous, one-size-fits-all perspective on combating societal tropes of the Black community and Asian community, or whether or not it’s fair to presume a widespread lack of solidarity, his lived experiences balanced with history of the solidarity within our communities undergird his views on the need for continued allyship.

The very wallpaper of The Black Dragon shares the journey of Asian Americans marching with the Black Panther Party and pushing the country toward equality. This space isn’t just where you can order flavorful chicken wings, it makes you critically think. In addition, the space expounds on the different Asian demographics found in Philadelphia.

Perhaps it’s the loss of oral tradition and collective memory– reminding both communities of their shared mutual respect and solidarity has led to instances of cultural misalignment over time. These tensions, further fueled by flashpoints of cultural clashes, have complicated the relationship.

The Black Dragon seeks to offer a glimpse into the shared heritage of both communities, a place where mutual understanding is the goal. As a change-agent and community advocate, Chef Evans seeks to honor said heritage in every aspect of his creative journey. Now, with the country spiraling from one terrifying headline to the next, the power of his voice in Philadelphia represents the leadership that is direly needed.

JW: “We are seeing a coordinated effort at the erasure of marginalized people. What do you feel is the path forward? How do we resist together?”

KE: “I truly believe organizing starts at the small and local levels and from there scaling to the citywide level, and from there continuing to build to tried and true organizations with statewide capabilities. Also, VOTE! Voting is forever going to be important, there are people who died for the right to get here.”

His answer is short yet evocative. As marginalized communities, the groundwork has been laid. Any impactful civil rights movement in the US organized thrived from scalable efforts that led to groundswell and impactful change. Chef Evans understands this and wants to see more scalable actions within our communities. Just like he listened to the community to improve the customer service experience, ensured crowd-favorites remained on the menu, and lessened wait times– the same mindset is needed for civic change. Listen to the people, make tangible changes, and get to work to make a difference.

Chef Evans’s love of Philadelphia and its residents, especially the Black community, is clear. Appropriation is not found within this space– rather he’s reclaimed the relationship between the Black and Asian community. He aims to ensure his space is a testimony to the positive effects of “one band, one sound” for civic change. Yes, you are going to get amazing infused cuisine here. But most importantly, you are going to be challenged to expand your mindset.

That makes The Black Dragon much more than a restaurant. It serves as a lighthouse, illuminating the power of solidarity and connection, one fried rice at a time.