The Voting Rights Act Is Under Threat. Here’s How We Got Here

The Supreme Court is about to finish what it started in 2013.

When the Supreme Court heard arguments last Wednesday in Louisiana v. Callais, hundreds of voting rights activists gathered outside. Inside, the nine justices were considering whether to eliminate the last major protection of the 1965 Voting Rights Act still standing.

The question before them sounds technical and confusing: Did Louisiana violate the Constitution by creating a second majority-Black congressional district? But actually the real question is simple: can states ever consider race when drawing maps, even to remedy discrimination?

The stakes could hardly be higher. If the conservative majority strikes down Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, up to 19 congressional seats currently held by Democrats could flip to Republicans as Southern states redraw their maps. The Congressional Black Caucus could lose 30 percent of its members. The landmark civil rights law that President Lyndon Johnson once called “one of the most monumental laws in the entire history of American freedom” would be reduced to a historic artifact.

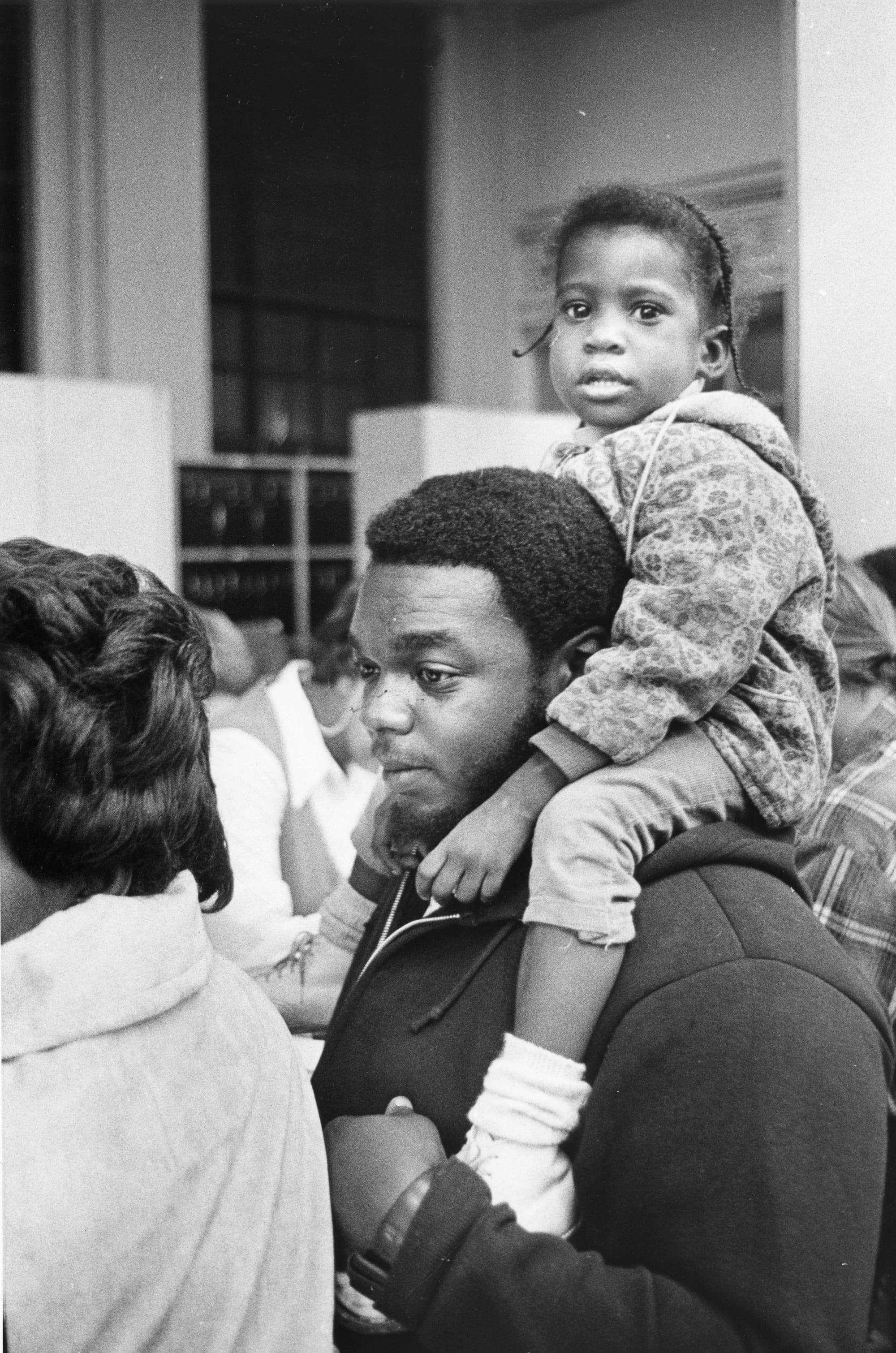

To understand how we arrived here, you need to know the history of the Voting Rights Act itself. When Johnson signed it into law on August 6, 1965, he was making good on a promise the 15th Amendment had failed to deliver for nearly a century.

That Reconstruction-era amendment, ratified in 1870, supposedly guaranteed Black Americans the right to vote. Southern states immediately set about undermining it through poll taxes, literacy tests, and political violence. By 1900, Black voters in the South had been almost completely disenfranchised.

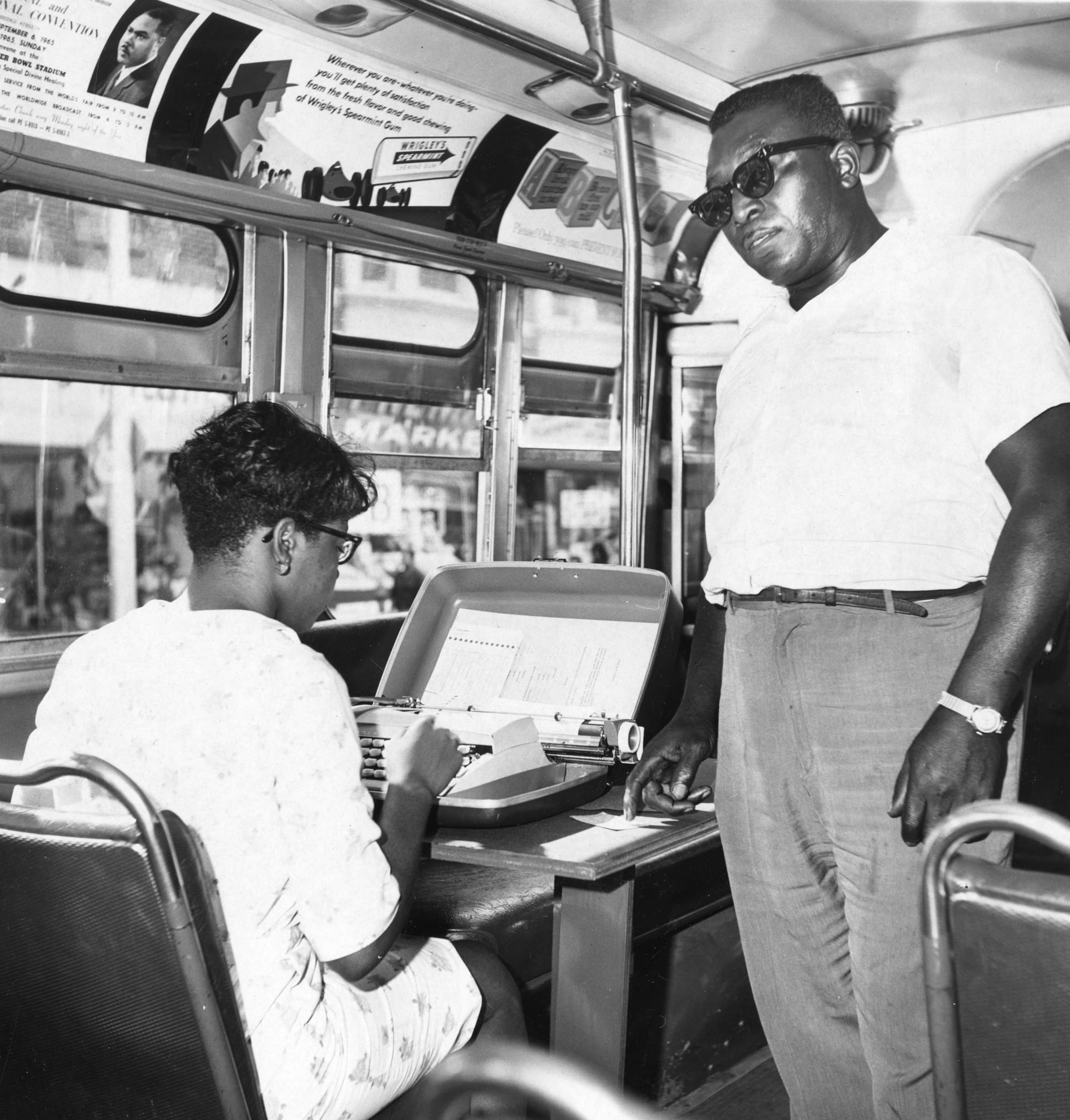

The 1965 law attacked this problem with two powerful tools. Section 2 banned any voting practice with a racially discriminatory effect, allowing individuals to challenge discriminatory laws in court. Section 5 went further, requiring states with histories of discrimination to get federal approval before changing any voting rules, also known as “preclearance”.

This “preclearance” requirement stopped discriminatory laws before they could take effect. Between 1965 and 2013, the Justice Department blocked more than 800 proposed voting changes. Within months of passage, a quarter million new Black voters had registered. The registration gap between white and Black Americans fell from nearly 30 percentage points to just 8 points within a decade.

Then came 2013. In Shelby County v. Holder, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for a 5-4 majority that the formula determining which states needed preclearance was outdated and unconstitutional. Roberts argued that voting discrimination was no longer the pervasive problem it had been in 1965. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, in her historic dissent, compared this reasoning to “throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

Ginsburg was prescient. Within hours of the decision, Texas announced it would implement a strict voter ID law. North Carolina followed the next day with sweeping voting restrictions. The laws remained in effect for years while civil rights groups fought them in court, disenfranchising countless voters.

Section 2 survived Shelby County. It remained the primary tool for challenging discriminatory voting practices nationwide. In 2023, the Supreme Court even upheld Section 2 in Allen v. Milligan, ruling 5-4 that Alabama had to create a second majority-Black congressional district. Louisiana, reading that decision clearly, drew its own map with a second majority-Black district during a 2024 special session.

That should have been the end. Louisiana has six congressional seats and a population that is roughly one-third Black. One majority-Black district clearly diluted Black voting power. Two districts seemed like an obvious remedy under Section 2, especially after Alabama.

“You think the drawing of this district was not predominantly based on race? It's a snake that runs from one end of the state to the other!”

Instead, a group of 12 voters describing themselves as “non-African Americans” sued, arguing the new map was an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. They claimed Louisiana had sorted voters primarily by race, violating the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause. A three-judge panel agreed, and the case headed to the Supreme Court.

At oral arguments in March, some conservative justices seemed to be having buyer's remorse about their Alabama decision just 28 months earlier. Chief Justice Roberts sounded incredulous: “You think the drawing of this district was not predominantly based on race? It's a snake that runs from one end of the state to the other!” Rather than issuing a ruling by June, the Court took the extraordinary step of ordering reargument and expanding the question. Now the justices are asking whether intentionally creating a majority-minority district violates the 14th or 15th Amendments.

The irony is brutal. Those amendments were passed after the Civil War specifically to guarantee equal rights for formerly enslaved people, including the right to vote. Now they are being used as weapons against efforts to protect minority voting power.

Louisiana has switched sides. The state now argues that considering race “in any form” during redistricting is unconstitutional. The Trump administration agrees, abandoning decades of Justice Department policy. Louisiana Attorney General Elizabeth Murrill complained that the law keeps “whipsawing us back and forth,” saying the Alabama decision essentially requires states to think about race “but you can't think about it too much.”

Conservative justices appear sympathetic. Justice Brett Kavanaugh, likely a swing vote, has previously argued that using race to remedy redistricting violations "should not be indefinite." During last week's arguments, he seemed receptive to Louisiana's argument that partisan gerrymandering is constitutionally permissible even if racial gerrymandering is not.

The logical endpoint is clear. If states cannot consider race when drawing districts, Section 2 becomes unenforceable in redistricting cases. States could draw maps that dilute minority voting power and simply claim partisan rather than racial motivations. Given that voting patterns remain highly polarized by race, the distinction would be meaningless in practice.

Sixty years after Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, the Supreme Court seems ready to complete the demolition it began in 2013. The umbrella Ginsburg warned about is being thrown away, and the storm has not passed.