Here’s What Mayor Parker Needs to Do to Defend Philadelphia’s History

Mayor Parker has more tools at her disposal than a lawsuit.

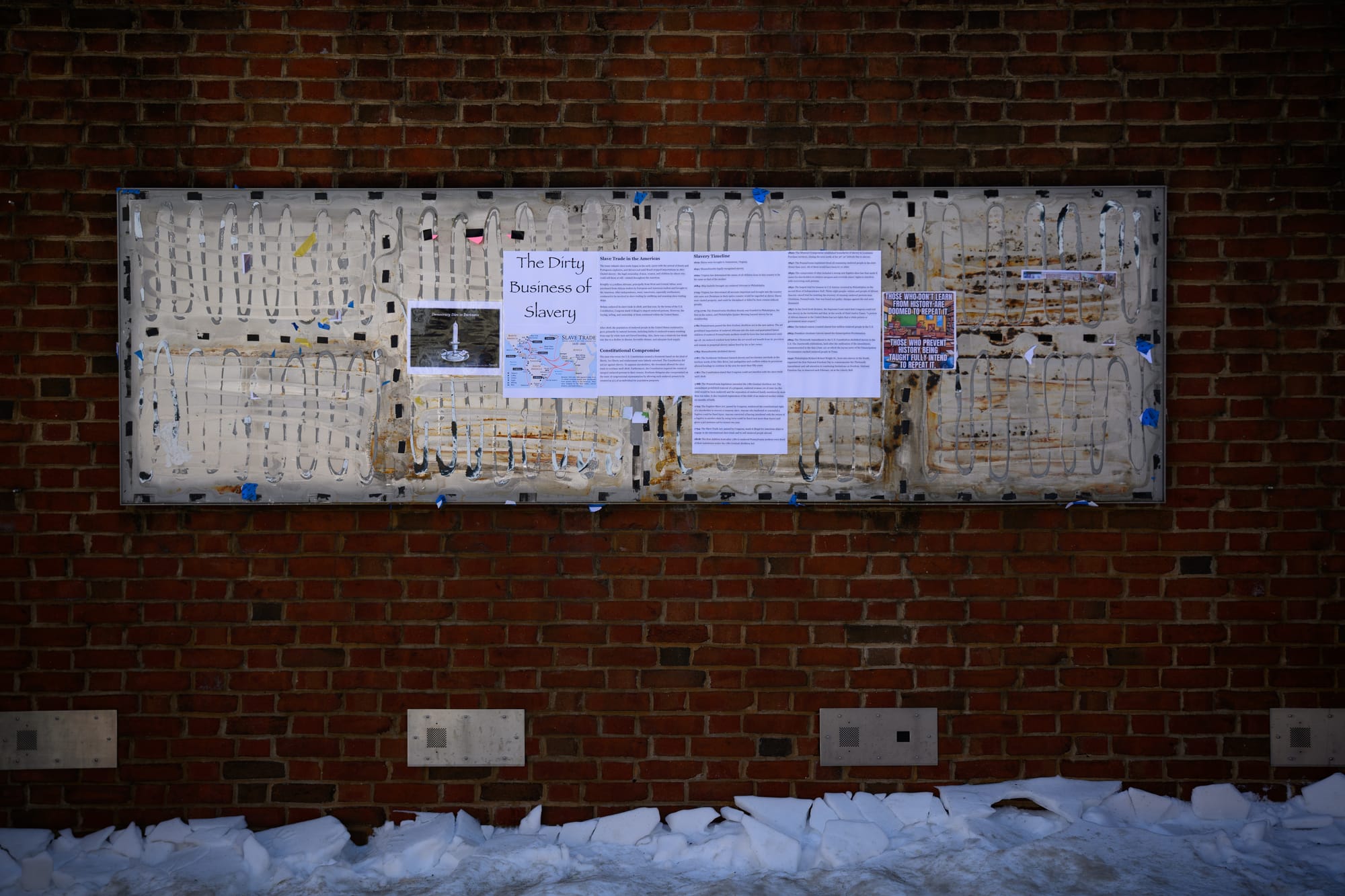

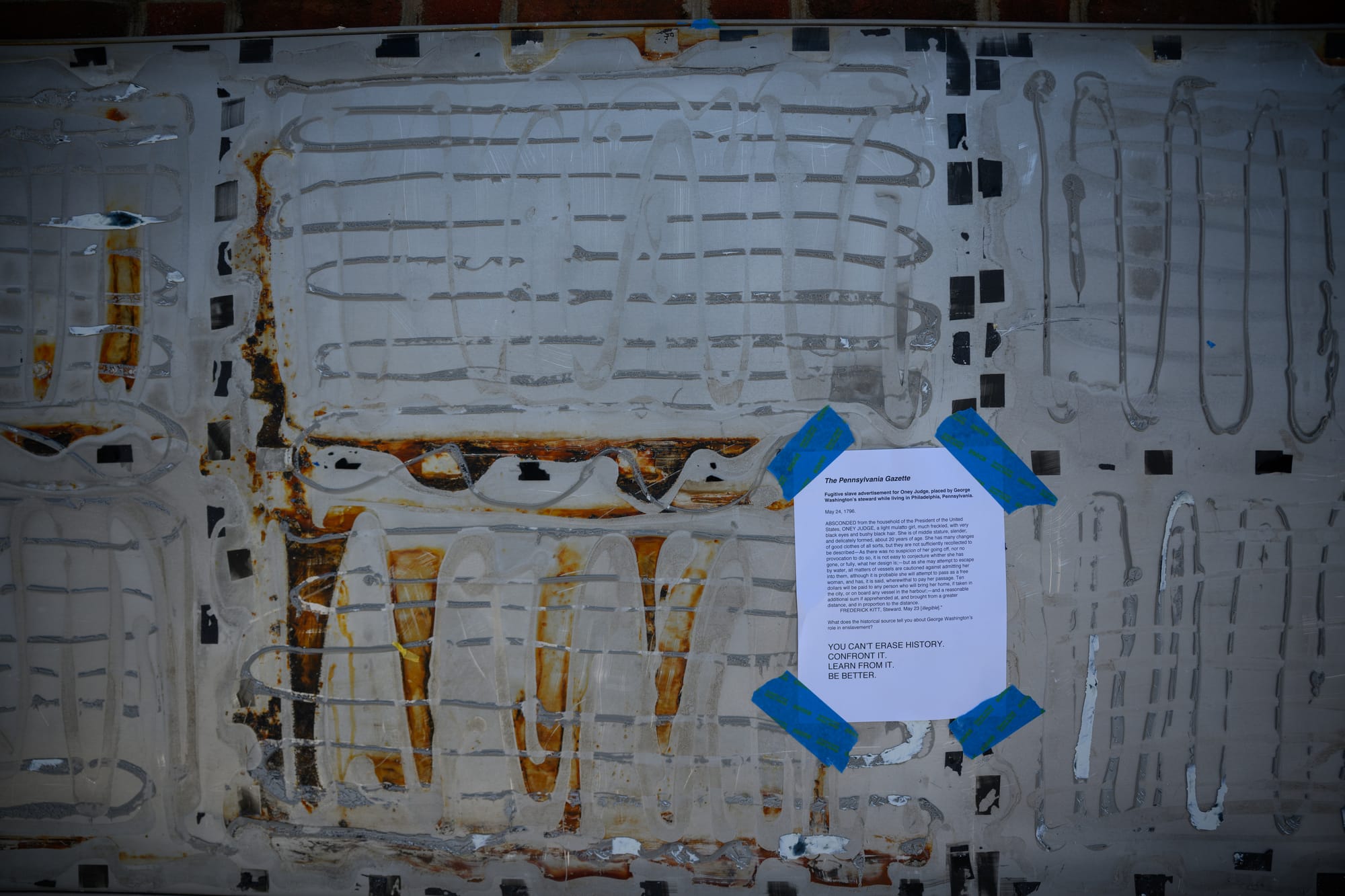

Visitors to Independence Hall can no longer read the names of the enslaved people George Washington held there while serving as president. The National Park Service quietly removed the slavery exhibits at the President’s House site earlier this year, erasing panels that documented how the nation’s founding ideals coexisted with human bondage at the very place where liberty is most loudly celebrated.

In response, the City of Philadelphia filed a federal lawsuit arguing that the removal violated a cooperative agreement governing the site. Mayor Cherelle Parker has expressed concern, city officials have spoken out, and protests have followed. But as this dispute drags on, the city’s response remains narrow and cautious, and I see it as insufficient at the moment.

This is a political test of whether Philadelphia’s leadership and the larger Democratic Party are willing to use their full power to defend an honest account of American history and to discuss the revitalization of America’s founding at a time when national leaders are deliberately trying to rewrite it.

The facts are straightforward. The President’s House memorial, created after years of activism and scholarship, was meant to confront a basic historical truth. The first president enslaved people while governing a nation founded on freedom. Acknowledging that fact does not erase George Washington's achievement as the first American president. It simply states what happened.

The exhibit named the enslaved people held at the President’s House and placed their lives in direct conversation with the Constitution being drafted just steps away. That context is now gone, removed by a federal administration openly hostile to what it labels “divisive history”. Philadelphia’s response has so far been limited to litigation, treating the removal as a contractual dispute rather than a civic emergency.

That choice reflects a broader Democratic Party habit that has become increasingly visible. When Republicans assert power over cultural institutions, Democrats default to process and refuse to articulate a different argument about said cultural institution. They sue. They wait. Maybe they protest. They hope the courts resolve what they are unwilling to confront politically.

Mayor Parker has more tools at her disposal than a lawsuit. The Mayor could condition city cooperation with federal events tied to Independence Hall. She could convene a formal commission on historical integrity tied to the nation’s upcoming 250th anniversary, inviting historians and scholars to talk about the history of the United States. She could work with the City Council to pass binding resolutions that set clear standards for how Philadelphia’s public history must be presented on city-controlled land.

Mayor Parker could push City Council or private donors to fund parallel installations or programming that ensure the story of slavery at the founding is told during the celebration of the 250th anniversary of the country. Instead, the city has largely confined itself to objections and legal filings, as if this were a routine dispute rather than a direct challenge to Philadelphia’s identity.

Democrats like Mayor Parker are reacting piecemeal. They frame each incident as an isolated overreach. They treat the problem as Trump’s problem, not as a long term contest over how the country understands itself. In doing so, they reveal a deeper failure. They have no affirmative vision for what the 250th anniversary should say about America, who belongs in its story, and what lessons it should teach.

Philadelphia should be leading that conversation. This city is not just another stop on the patriotic tour. It is where independence was declared, where the Constitution was drafted, and where the contradictions of the founding are impossible to ignore. If slavery can be erased here with minimal resistance, it can be erased anywhere.

I have been thinking a lot lately about what it means to talk about the founding of the United States and American dynamism in the country’s 250th year. Given that some historians argue that empires last 250 years, it seems America is close to eclipsing that benchmark. In that context, I keep coming back to David Blight’s sprawling biography of Frederick Douglass, a reminder of how the most important American voices have often argued with the country in order to claim it. Douglass did not flatter the founding. He attacked its hypocrisy with precision, yet he still treated the nation’s stated ideals as real tools to expand American power for good. That is the tradition Democrats and liberals keep forgetting they have.

There is no shortage of figures who show how to speak about American ideals as a force for good without lying about the country’s sins. Martin Luther King Jr. made the founding language inseparable from a demand for full citizenship. John Adams believed in republican government fiercely enough to distrust kings and mobs alike. Abraham Lincoln treated the Declaration’s promise as something the country owed to people it had excluded.

Franklin Roosevelt built a new baseline of economic security and called it freedom. Fannie Lou Hamer insisted that democracy meant more than speeches and ceremonies; it meant power for the people who had been shut out.

The point is not to place these figures on a pedestal, none are perfect and some have their own controversies. But what all of these figures offer is a usable political language, one that can celebrate the country’s possibilities while staying honest about how hard the country has fought against its darker impulses.

And the response from those who do not think the Mayor could do more is one word: pragmatism. Federal land, federal authority, federal courts. But that logic misunderstands power. Public history is not only shaped by ownership. It is shaped by political will, by pressure, and by the refusal to accept silence as neutrality.

Black History Month is often treated as a time for reflection, but reflection without action can become an “empty ritual” as Ta-Nehisi Coates has written. The removal of the slavery exhibits is not a symbolic loss. It materially alters what millions of visitors learn about the founding. It teaches them that slavery was peripheral rather than a central moral issue that this country fought a war over, in which over 500,000 people died.

If Democrats like Mayor Parker want to argue that American democracy is worth defending, they need to show that they are willing to defend its full history. The fight over the President’s House is about whether this city, and the party that governs it, is prepared to shape the story of the nation’s future rather than simply react to those trying to erase its past.