Rest For The Weary: On Black Voter Exhaustion

How do we move from this moment of profound disappointment?

During the pandemic, I moved into an apartment on Lombard between 13th and Broad Streets, residing in the area for the first time since I was a child. By this point, I had come to embrace the area as the historic Seventh Ward, the neighborhood that W.E.B. DuBois immortalized in his landmark sociological study The Philadelphia Negro, that region from Sixth Street to 23rd Street east to west, and from South Street to Spruce Street in the other direction.

I walked around the abutting neighborhoods of the historic Seventh Ward and saw iron placemarks denoting the Institute for Colored Youth, and the home of Frances E.W. Harper, a noted abolitionist, poet, scholar, and suffragist who was proud to be from here. I read Saidiya Hartman’s accounts of this zone in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments and got excited about my place of origin all over again, and demoralized about how gentrification robs us of palpable continuity. As energizing as that period was, it was also enervating.

I’m a writer, having inherited both of my parents’ artistic inclinations. I have attended this city’s public schools and universities, and gratefully accepted its grants and scholarships. Although I’m currently living in New York City, I’m constantly drawing from the wealth of ideas and energy in Philly’s firmament. I have learned from the social practices of other Black residents, most of them being members of my family — the stories told on street corners and within public parks, the resilience of those displaced by the implosion of some of the city’s high-rise projects, the white carriages carrying deceased ward leaders off to heaven’s gate. I’m a product of whatever promises this city has to offer.

In the wake of the 2024 presidential election, so much of what made me who I am appears to be at risk in this period of social and economic retrenchment.

Five years ago, in a debate with Joe Biden, Trump disrespected the entire city and sowed distrust in its election processes, claiming infamously that “Bad things happen in Philadelphia.” And now, the president’s administration is rolling back federal funding to local colleges and universities, raiding Latinx and Black social and work sites, and enacting policies that prohibit protests and other types of gathering in public spaces. What remains in question is how much of the city’s social fabric will be disturbed by these acts of repression given how much has happened already.

Amid DEI rollbacks and the administration’s purge of the federal government, over 300,000 Black women have left the workforce this year. The Trump administration has already begun to deregulate the Environmental Protection Agency and roll back legislation that will disproportionately impact poor Black and Brown communities. It’s enough to cause whiplash.

As ICE agents descend on Latinx and Black communities in Chicago and Philadelphia and other cities, the roll call sounds a lot like the litany of Northern cities Fannie Lou Hamer listed in her famous December 1964 speech, where she uttered the line, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired.” The quote is scathing in its critique of towns “up North”: “Quit saying that we are free in America when I know we are not free. You are not free in Harlem. The people are not free in Chicago, because I've been there, too. They are not free in Philadelphia, because I've been there, too. And when you get it over with all the way around, some of the places is a Mississippi in disguise.”

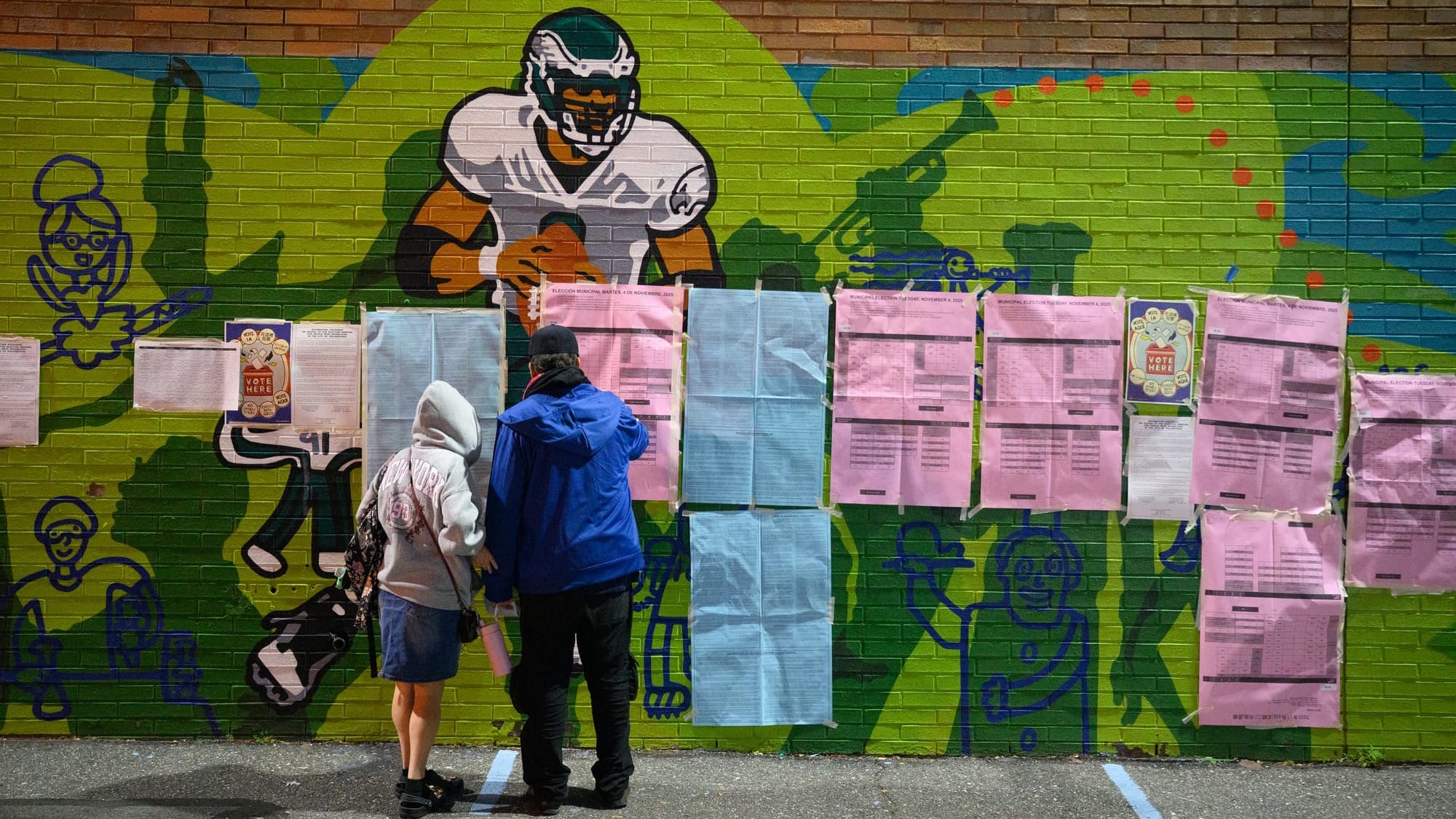

As it stands, Hamer’s phrase has itself been exhausted, slowly recirculating like a lullaby for the aggrieved. Black people are experiencing rampant voter exhaustion, especially in a battleground state like Pennsylvania. While some experts label some candidates anti-democratic and others not, many Black Philadelphians are tired of casting what could be deciding votes over the country’s future.

Some of us are too tired to join the effort, and others of us have chosen to opt out rather than to participate in a process we deem unethical. In an op-ed for Truthout, writer Rashida James-Saadiya explained that,

“exhaustion is a strategy. What looks like collective fatigue is actually the consequence of a carefully engineered mechanism designed to rob us of our power — our power to resist, to imagine, to protect each other and to create sustainable change. Burnout is many things, including an effective political tool for our oppressors.”

In the immediate wake of the 2024 presidential election, news outlets reported on Black American political apathy, which is perhaps an expression of ongoing exhaustion. These postmortems reflected that all the prognosticating about Black men’s presumed mass rightward march were unfounded, possibly spread by bad-faith actors and influencers. According to the Pew Research Center, only 59% of eligible Black voters showed up at the polls last November. There is a mode of assessing and cataloguing the choices made by Black voters that feels in league with every social study ever recorded of Black life — a way of shaming and blaming beleaguered communities.

Not all of these reports are pathologizing. In a piece published in The American Prospect, Gabrielle Gurley described the fatigue afflicting Black Philadelphia communities. She pointed to strategic disinvestment in Black neighborhoods, the gentrification of West Philadelphia’s major commercial corridor, the low voter turnout in the 2023 mayoral election, and young voters’ disengagement as trends that city leaders and Democratic Party officials crucially ignored.

It feels like we’re in another dispiriting cycle — yet another instance of retrenchment burned in our cultural memory, from the bleak years after Reconstruction, to the fallout of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, to the post-Reagan carceral state.

In Wayward Lives, Hartman attends to Black hubs like Philly and Harlem, paying special attention to the former, as she positions herself in dialogue with Du Bois’s Philadelphia Negro. Describing the city’s esteem at the time Du Bois began his study, Hartman writes, “Since 1780, Philadelphia had been a laboratory for the nation’s experiment in racial democracy and the premier stage on which the future after slavery was enacted.”

If we look at our history, in so many ways, Philadelphia has been a bellwether for the rest of America, and for Black America in particular.

It’s where a charismatic young political activist and teacher at the Institute for Colored Youth named Octavius Catto changed the course of history, fighting for Black suffrage and desegregation in the 1860s. His protests, especially those coordinated in concert with his fiancée Caroline LeCount, presaged acts of civil disobedience that would be deployed popularly a century later.

In a 1977 article published in the journal Pennsylvania History, evaluating another period of political stagnation, the historian Harry C. Silcox writes that the murder catalyzed “the rapid retreat of most Blacks from politics.” Further, Silcox explains, “Catto's death brought to an end Black militant behavior in nineteenth-century Philadelphia.” Maybe Black political activity didn’t vanish, it simply went underground. Nevertheless, his assessment might speak to the ways that collective grief can stall momentum.

In this new nadir, how do we move from this moment of profound disappointment? If politics as usual is no longer viable, what might other strategies look like at this time? Instead of returning to the same old political playbooks, what might it look like to do things differently?

The late legal scholar Robert Cover offered a theory in the 1980s where some groups might be “jurispathic” or law-killing, or “jurisgenerative,” creating new codes easily. To Cover, our courts are jurispathic: When a judge interprets the law while presiding over a case, through their decision, in that moment, they select one pre-existing meaning that squelches new possibilities. On the contrary, in communities like ours, Cover observed, the capacity for new laws exists naturally through culture:

“We constantly create and maintain a world of right and wrong, of lawful and unlawful, of valid and void.”

In this moment, as we watch the news for U.S. Supreme Court decisions, and as Pennsylvania prepares for this upcoming state Supreme Court retention race, we know we are living at the mercy of very powerful people’s interpretations. But, as Cover’s work teaches us, rule-making emerges from everyday people, not the top-down arrangement we’re always taught. And new codes and norms flow out of Black social life when people get together, in ways that could be conscious or not, according to theorists Fred Moten and Stefano Harney.

Cover argues that narratives help to form our basis of reality — which we uphold or rebel against in the process of making new laws. According to Temple professor Linn Washington, Philadelphia is the home of Black America’s first published counternarrative. This city, full of rebellious lawmakers and breakers, has always challenged the single story this country likes to tell about itself.

Next year will represent the 250th anniversary of the drafting and signing of the Declaration of Independence. What other narratives about the country’s history might emerge and proliferate in the semiquincentennial?

The proceedings are likely to be invigorating for some, and exhausting for others. In this moment of voter fatigue, I look to guidance from the Black Rest Project and the Nap Ministry. Rest can look all sorts of ways, like a siesta, or a workshop, or a summer break. Whatever happens on the other side of rest requires energy, creativity, and collectivity. As history slowly repeats itself, whether that looks like a boycott, or a protest or a party is up to us.