How Philadelphia Became One of the Most Carceral Cities in the World

Before the War on Drugs, there was the War on Crime, and before the War on Crime, there was the War on the Poor. Black Philadelphia families have been tasked with surviving each siege.

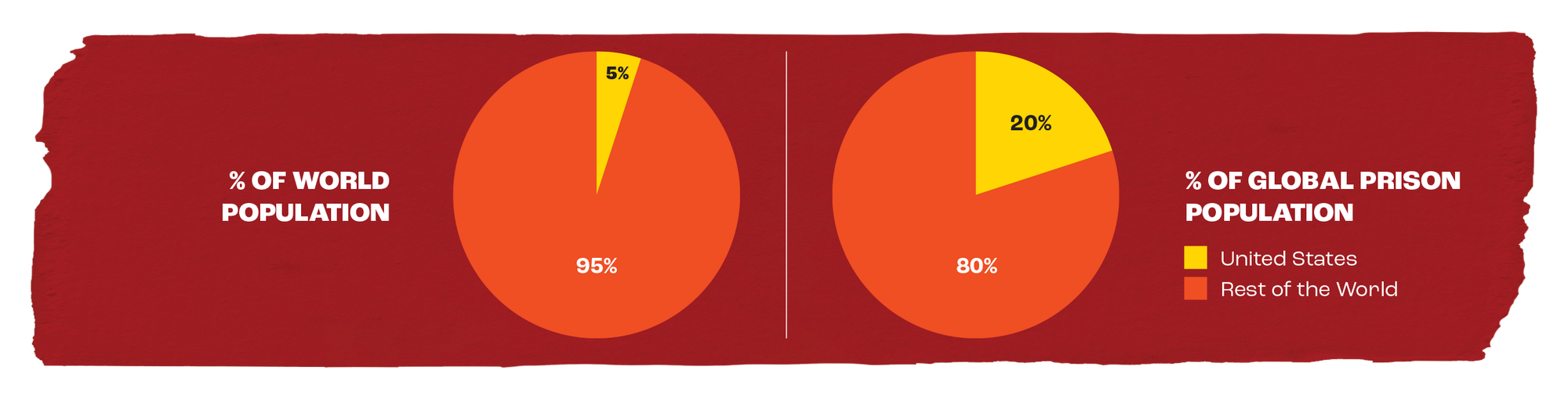

Today, the United States holds more than 20% of the global prison population despite comprising only 5% of the world’s population. In America, our federal government spends over $80 billion on incarceration each year while local, state, and federal governments spend approximately $20,000-50,000 annually to incarcerate an individual. Philadelphia is one of the top carceral cities in the world. In fact, Philadelphia’s District Attorney’s Office (DAO) is the largest prosecution office in Pennsylvania and the third largest in the country with roughly 300 lawyers on staff.

From the 1980s to 2017, the mass incarceration of people in jails and prisons increased by 500% nationally, but in Pennsylvania the rate was over 700%. Philadelphia’s history of tough-on-crime policing has definitely shaped its carceral identity, but state laws and politics have facilitated the mass incarceration of marginalized groups. Since the 1970s, Pennsylvania legislators have increased the number of criminal offenses from 282 to nearly 1,500. In 2017, Philadelphia’s high rate of adults on on probation or parole made it "the nation's most supervised big city"

Although Pennsylvania Supreme Court cases like Commonwealth v. Bradley (1972) temporarily succeeded in making capital punishment unconstitutional, by 1978 the legislature edited the death penalty bill and received approval from the Pennsylvania and U.S. Supreme Courts to reinstate the controversial sentencing. With this significant increase in carceral legislation, Philadelphia had been the only big city in the Northeast region of the United States to legally sentence countless juveniles to life imprisonment and even death row until Governor Tom Wolf (2015-2023) declared a death penalty moratorium in the state in 2015.

In 2017, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court supported this move toward decarceration in Pennsylvania by ruling unanimously that life sentences for juvenile offenders without parole was unconstitutional. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court argued that the sentence was “not appropriate” because a juvenile’s “transient immaturity” makes it difficult for prosecutors to successfully argue that a murder committed in adolescence was “deliberate,” “premeditated,” or the result of a “permanent” character trait of violence.

This new direction toward decarceration has ebbed and flowed for nearly fifty years in this state. Even today, Pennsylvania is moderately regressing back toward mass incarceration because Governor Josh Shapiro has only approved roughly 50% of the clemency applications the Board of Pardons has placed on his desk, compared to former Governor Wolf who approved almost all the recommended applications placed before him during his second term.

Philadelphia’s poverty rate is approximately 19.7% with many of the same neighborhoods suffering from concentrated poverty, also experiencing high crime, over-policing and in some cases under-policing. The issues of double victimization and racial capitalism disproportionately affect poor communities of color in regard to crime and policing. Poor, Black communities often face double victimization through government neglect and economic exploitation, but are also blamed for crime, real and imagined.

No one can predict the decisions politicians will make once they hold public office. However, it takes an informed public that is educated on the issues and passionate about social change for the betterment of society to pressure politicians to fight on our behalf for causes that matter, like an end to poverty, criminalization, and mass incarceration.

The tolls of many wars

On September 28, 2022, the Public Interest Law Center of Philadelphia (PILC) and the Prison Policy Initiative released the report, “Where people in prison come from: The geography of mass incarceration in Pennsylvania,” in which they detailed how Philadelphia sends the most people to prison in Pennsylvania at a rate of 463 per 100,000 residents. The report also suggested that historic racial segregation and inequality in Philadelphia has played a role in the neighborhoods most affected by mass incarceration when it identified the majority Black, low-income North Philadelphia neighborhood of Nicetown-Tioga as where residents are “more than fifty times as likely to be imprisoned” than residents of the majority white and middle-upper class “Center City-West neighborhood.”

As a result of the War on Drugs’ race and class bias in policing, arrest, and incarceration, today Black people are 10 times more likely than white people to be incarcerated for drug offenses even though both groups use drugs at approximately the same rates. Aside from incarceration due to drug-related crimes, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) estimates that general rates of imprisonment remain racially biased since 1 out of 3 Black boys, 1 out of 6 Latino boys, and 1 out of 17 white boys today are likely to go to jail or prison in their lifetime.

According to the Brennan Center, in 1980, Pennsylvania was incarcerating 8,171 people. The number of people inside state prisons more than tripled by 1992, Brennan analysis indicated, rising to 24,974. In 2013, the state system would hold 50,312 people in prison.

But before the War on Drugs, there was the War on Crime, and before the War on Crime, there was the War on the Poor. Black Philadelphia families have been tasked with surviving each siege.

The transitions of the late 1960s

Since 2018, the incarceration rate of juvenile offenders decreased by 70%, and reduced incarceration years have dropped by almost 50% by utilizing probation for criminal offenders who were affiliated with a felony-murder case but did not kill anyone. In that same time frame, Philadelphia has witnessed a 25% decrease in the murder rate. Current DAO initiatives seek to undo the tough on crime program Philadelphia pursued in the 1960s.

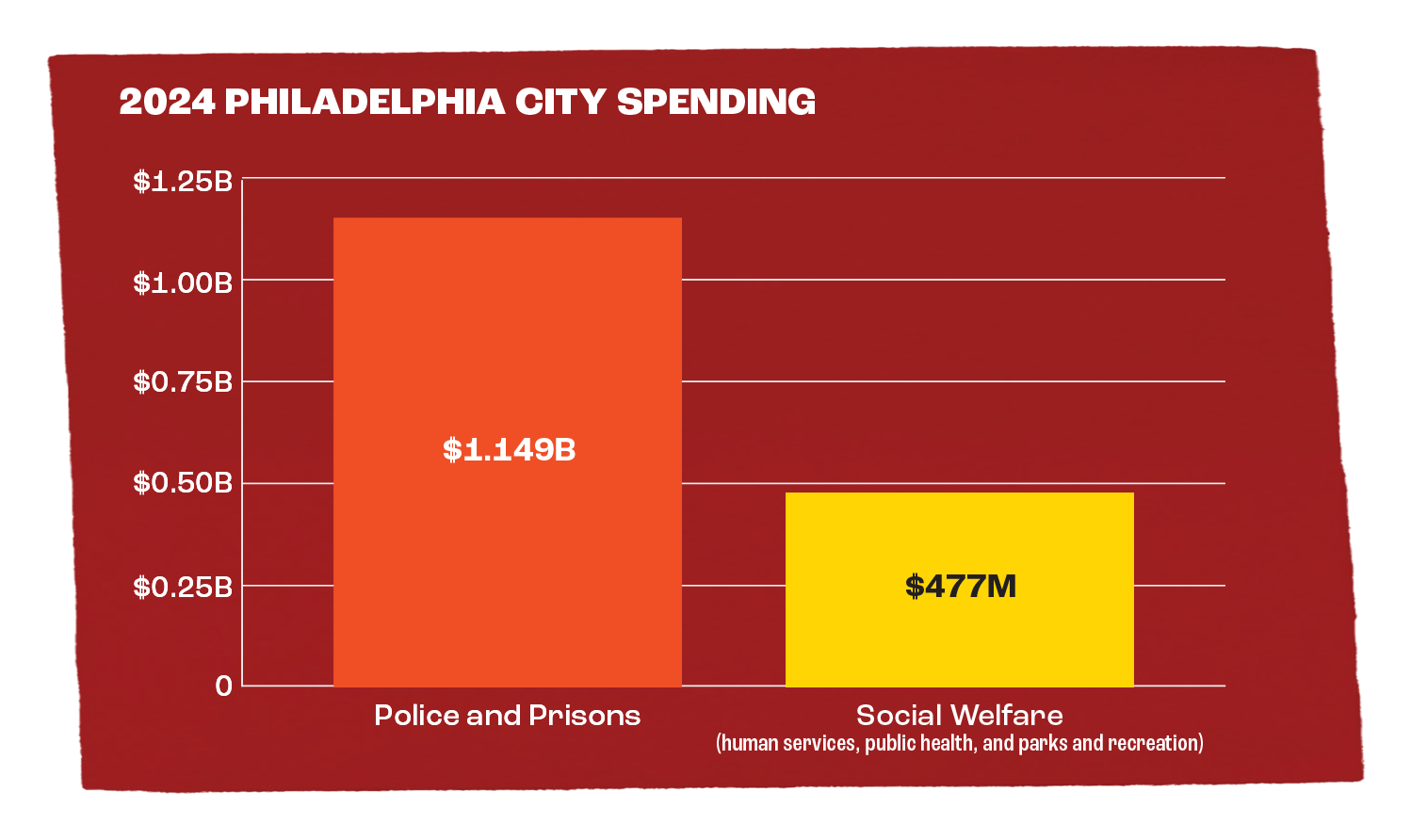

City governments like Philadelphia’s have had the ability to reduce crime through poverty alleviation initiatives like decent housing, education, and jobs, for generations, but they refuse to wholeheartedly do so and instead invest in the police department and corrections to curb crime. In 2024, the city of Philadelphia spent approximately $1.149 billion on police and prisons while it spent only $477 million on social welfare, such as human services, public health, and parks and recreation.

This system of racial capitalism involving the overfunding of police and the underfunding of social welfare programs that could lift people out of poverty creates social conditions that lead to higher rates of poverty-induced crime, Black incarceration, Black unemployment, and Black recidivism.

It’s been this way for generations. Looking back at the 1960s, unfortunately, the Black underclass still suffered greatly from institutional racism and rapid deindustrialization that led to thousands of manufacturing jobs in the inner city disappearing because of automation and decentralization, positions migrating to the car-dependent suburbs, or factories closing altogether during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Additionally, the Black underclass did not possess the post-secondary education, employment, wealth, and networking privileges held by the Black middle-class to lift themselves out of poverty. While federal social welfare programs addressed some of the socioeconomic issues that affected the Black community, peaceful protests, demonstrations, and even violent uprisings against segregation and racial discrimination, the Vietnam War, and police brutality nationwide were necessary in the pursuit for first-class citizenship. However, those actions often inspired local, state, and federal governments to use police power to manage crowd control and reestablish “social order.”

Nevertheless, the Civil Rights Movement (1954-1968) opened the door to racial equality in America, but community activism through the Black Power Movement along with community participation in the electoral process were necessary to ensure racial equity for all Black people regardless of their class status. Through voting, Black Americans have the power to elect local and state officials who can fight for causes and pass legislation that can improve the socioeconomic conditions of the entire Black community, especially the Black working-class and poor.

In America, first-class citizenship is a delicate status to possess. Extralegal violence in the forms of lynching, race riots, and residential mob violence against desegregation solidified white supremacist control of the polls, public office, and the court system. The Civil Rights Movement’s boycotts, direct action protests, pickets, and civil disobedience demonstrations were necessary to “agitate” for the passage of The Civil Rights Act of 1964 under President Lyndon B. Johnson, which established equal opportunity employment for all and enabled the Black middle-class to double in size during the 1960s.

In 1967, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (led by Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, Jr.) released the Kerner Commission Report which identified white racism and racial disparities in education, employment, housing, and policing as the causes for approximately 250 racially motivated riots nationwide, particularly in response to local incidents of police brutality. From 1968 onward, the assassinations of civil rights leaders like Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. sparked additional uprisings, which led federal officials to believe people of color were undeserving of social welfare and should be contained and controlled through a War on Crime initiative. This mindset of Black criminalization was also adopted by local governments.

On June 19, 1968, Congress passed the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968, which led to the creation of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) that offered $100 million in grants to states and $50 million to local governments to fortify their police departments with military equipment or spend the funds on anticrime and antigang programs to prevent riots, organized crime, and gang violence. Therefore, when big cities faced budget deficits due to their dwindling tax base, city officials defunded social welfare programs, but used their limited revenue and federal grants from the LEAA to increase spending on policing and prisons.

Since Republican and Democratic government officials largely sought tough on crime policing and incarceration to resolve racial uprisings and poverty-induced crime, community activists have often chosen to solve poverty through communal, grassroots programs and by electing politicians who supported their causes.

The federal government’s immediate transition from a War on Poverty to a War on Crime during the 1960s inspired state and local governments to manage crime by simultaneously using LEAA grants and city budget funds for not only anti-poverty and anti-crime programs for youth, but also new surveillance technology and “military-grade weapons” for police departments.

Enter Arlen Specter

In 1968, Philadelphia District Attorney Arlen Specter (1966-1974), a liberal-minded politician who would serve as a Republican and a Democrat throughout his political career, pursued justice on many fronts that included halting violent crimes against youth and adults. While Specter supported community-oriented, recreational activities, therapy sessions, mental health programs, drug rehabilitation, and anti-gang programs to curb various forms of poverty-induced crime in Philadelphia, his DAO prioritized tough on crime policing and incarceration of people convicted of a crime.

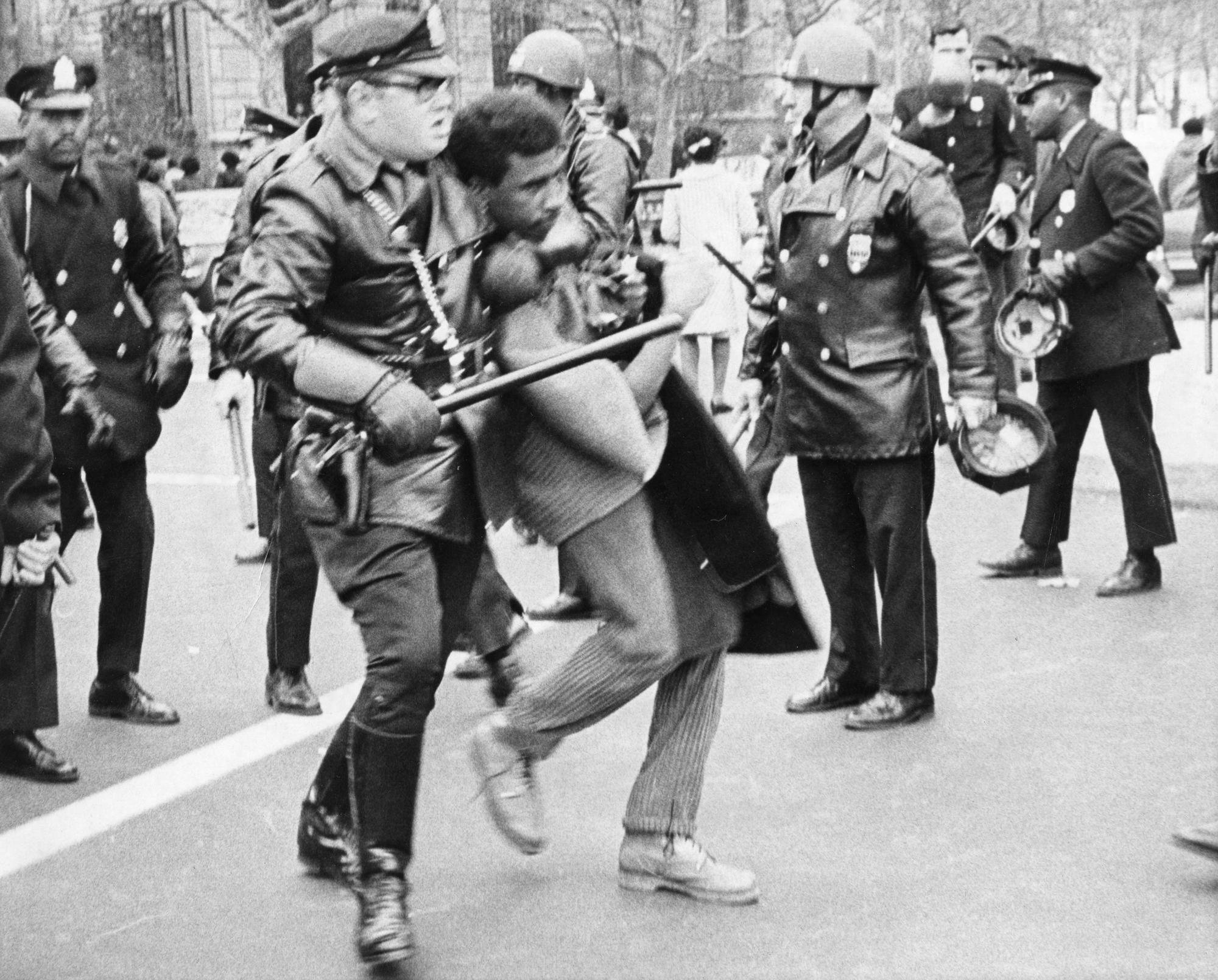

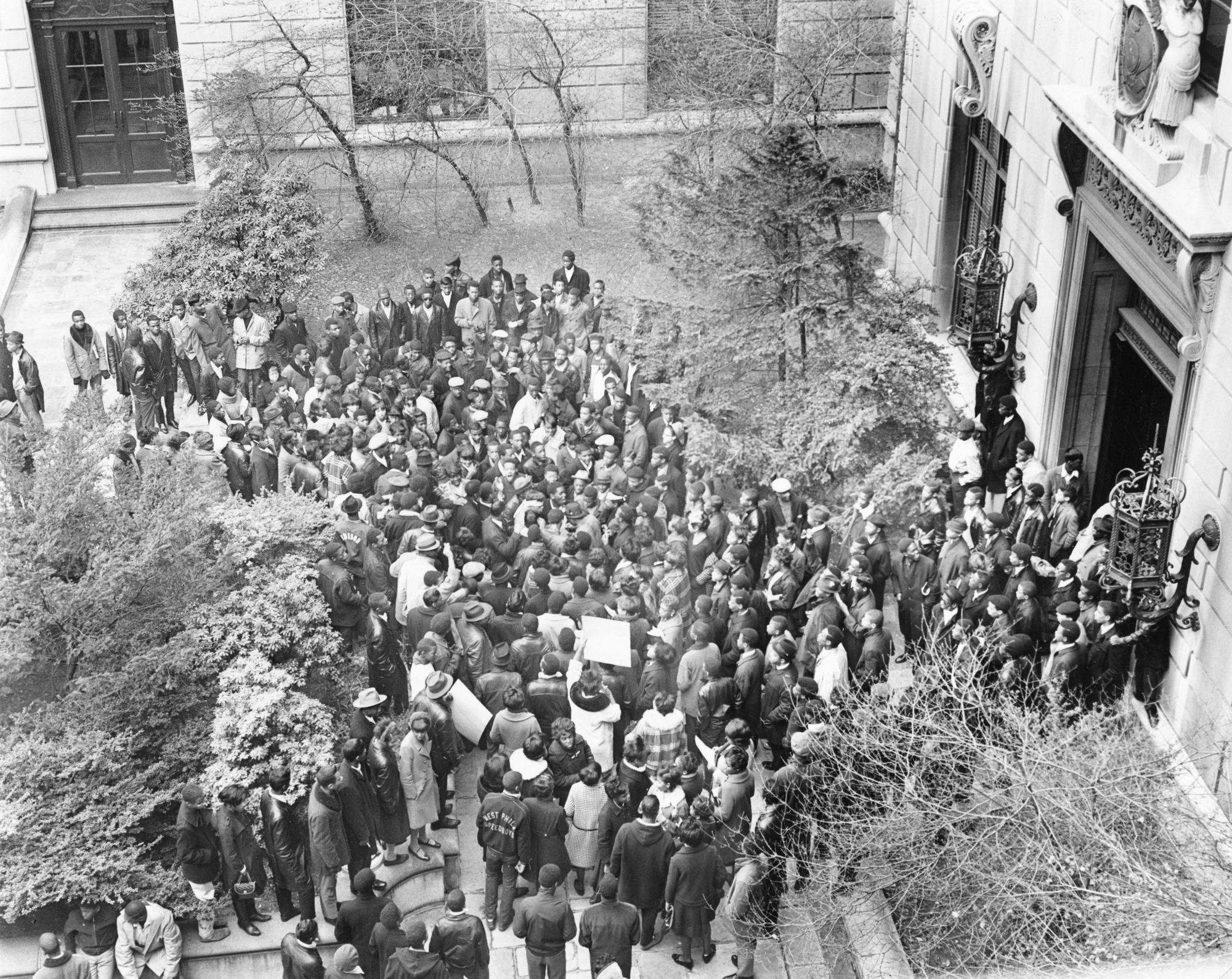

In fact, Specter’s tough on crime approach often dovetailed with Police Commissioner Frank L. Rizzo’s (1967-1972) stance on fighting crime. On November 17, 1967, approximately 3,500 middle and high school students and other community leaders held a demonstration at the Board of Education building to demand more African American History classes in their school curriculum, more Black teachers and principals, the removal of police from schools, and better school conditions.

Although demonstrators in the November 1967 Black Student Walkouts viewed the protest as peaceful, Rizzo thought the demonstration was out of control once a male demonstrator ran on top of cars parked in front of the building and more demonstrators joined the protest and banged on cars and windows. He then ordered 111 new police sergeants to “protect” plainclothes officers stationed at the picket to charge, beat with billy clubs, and arrest youth and adult protestors for “rioting.” Approximately 20 to 30 demonstrators were injured due to police brutality and 57 people were arrested.

In the civil suit Terry Heard v. Frank Rizzo and Arlen Specter, demonstrators who argued the police and district attorney had violated their civil rights during the picket with police brutality and prosecution won their case in the U.S. District Court. However, the victory was short-lived and the tough on crime program of both Rizzo and Specter was later reaffirmed when the U.S. Court of Appeals and Supreme Court ruled in favor of the police and DAO, allowing them to lawfully indict, try, and convict demonstrators who allegedly hindered the police’s ability to control an “explosive situation.”

As a result of this approach to reduce crime, real and imagined, Philadelphia’s crime rate in 1968 actually increased by 2.5% from 1965, just as its poverty rate was also increasing to approximately 15.4% by the 1970s. From 1966 to 1968, Specter’s DAO sought longer sentences for serious crimes supported by substantial evidence. In response, defense attorneys demanded that their clients receive jury trials, leading to the number of jury trials increasing from 77 in 1965 to 189 in 1968 at a rate of 132%.

In 1968, Specter’s DAO tried 13,351 cases, which was the highest number of trials ever prosecuted in the city’s history at that time.

The DAO increased the conviction rate to 70%, reduced the criminal trial backlog, pursued a narcotic drug sales probe, prosecuted bookstore owners for selling pornographic literature to minors, and cracked down on consumer fraud schemes like loan-sharking and false insurance claims. Specter’s DAO maintained Pennsylvania’s mandatory minimum sentencing law, the Drug, Device and Cosmetic Act of 1961, which meant that drug dealers could receive 5-20 years in prison for their first offense, 10-30 years for their second offense, and life in prison for their third offense. If convicted of possessing narcotics, drug users could receive up to 5 years in prison for their first offense, up to 10 years for their second offense, and up to 30 years in prison for their third offense.

The DAO even implemented three new programs that predicted the exact days when police officers and witnesses had to appear in court to testify during criminal trials or had staff who could contact these individuals if a case was settled under a guilty plea. This initiative saved the city over $211,000 in spending on police overtime and prevented more than 7,000 police officers and countless witnesses from wasting over 70,544 hours in unproductive court time.

In 1968, Specter’s DAO also attempted to curb alcoholism and drug addiction through rehabilitation rather than incarceration. During that year, approximately 43% of the 97,688 people arrested by the Philadelphia Police Department were picked up for intoxication. In response to this supposed rise in substance abuse that appeared to be increasing since 1967, Specter collaborated with police, hospitals, health service organizations to craft what would become a citywide Mental Health and Mental Retardation Plan. The mental treatment for alcoholism program the DAO helped foster would focus on diagnosis, detoxification, hospitalization, psychosocial evaluation, and in-patient and out-patient, long-term rehabilitation. Additionally, incarcerated substance users in county and state prisons were recommended for group therapy as a form of rehabilitation.

The long journey towards Safe(r) Streets

In 1969, the New York Times declared Philadelphia the “gang capital” of America because it had approximately 70 well-documented gangs by the police department and the highest rate of gang-related violence in the country: 45 murders and 267 injuries involving gang members and innocent bystanders. The rise of gang murders in the Black neighborhoods of North and West Philadelphia encouraged city officials, police, and community activists to work together to implement a rehabilitative anti-gang program rooted in sociological research. During the 1960s, there were more than 200 juvenile gangs in Philadelphia. Approximately 96 percent of gang-affiliated youth from groups like Valley, Sommerville, 13th Street, and the Moons were Black.

In Summer 1968, a series of incidents in North Philadelphia encouraged community residents and politicians to invest in a program to end gang violence. When news spread that a boy was shot and killed in a gang fight and gang rivals, Zulu Nation and the 8th and Diamond Streeters had declared war, Yorktown residents sent a message to the DAO asking for help. On Independence Day, residents and staff from the DAO met with leaders of both gangs on a North Philadelphia street corner to end the violence. Following this series of incidents, politicians became more interested in finding a remedial solution outside of policing to address gang activity in the city.

From 1969 to 1976, Safe Streets, Inc. operated as a bipartisan, community organization that recruited police officers and gang workers from juvenile gangs like Zulu Nation and the 8th and Diamond Streeters. But none of this non-carceral activity was possible without voters pressing political officials to find ways to rehabilitate their community rather than over-police and incarcerate its members.

When Rizzo served as mayor from 1972-1980, to some residents, white and Black, Philadelphia had the appearance of a safer city. In actuality, by 1976, Rizzo’s mayoral administration oversaw city budget spending for the police and prisons increase by 90 and 110 percent of their 1970 figures, with each department receiving $152.5 million and $18.8 million, respectively.

Unfortunately, crime persisted and police-community violence continued in the 1980s as society became less economically collectivist and racially integrated. President Ronald Reagan’s “trickle-down” economics policy that lowered corporate and estate taxes while providing tax benefits that included retirement savings, lower mortgage rates, and charitable giving incentives for the wealthy disadvantaged the lower and middle classes who paid higher taxes but received few tax breaks and inefficient government services.

From approximately 1977 to 1998, the national Cocaine Epidemic not only sparked a rise in theft, drug dealing, drug possession, gun violence, and murder, but also triggered Reagan’s War on Drugs that overpoliced lower-income, urban (Black) neighborhoods for drug-related crimes instead of white suburban communities that were often humanized for their drug offenses with the offering of rehabilitation instead of incarceration.

The future ahead of us

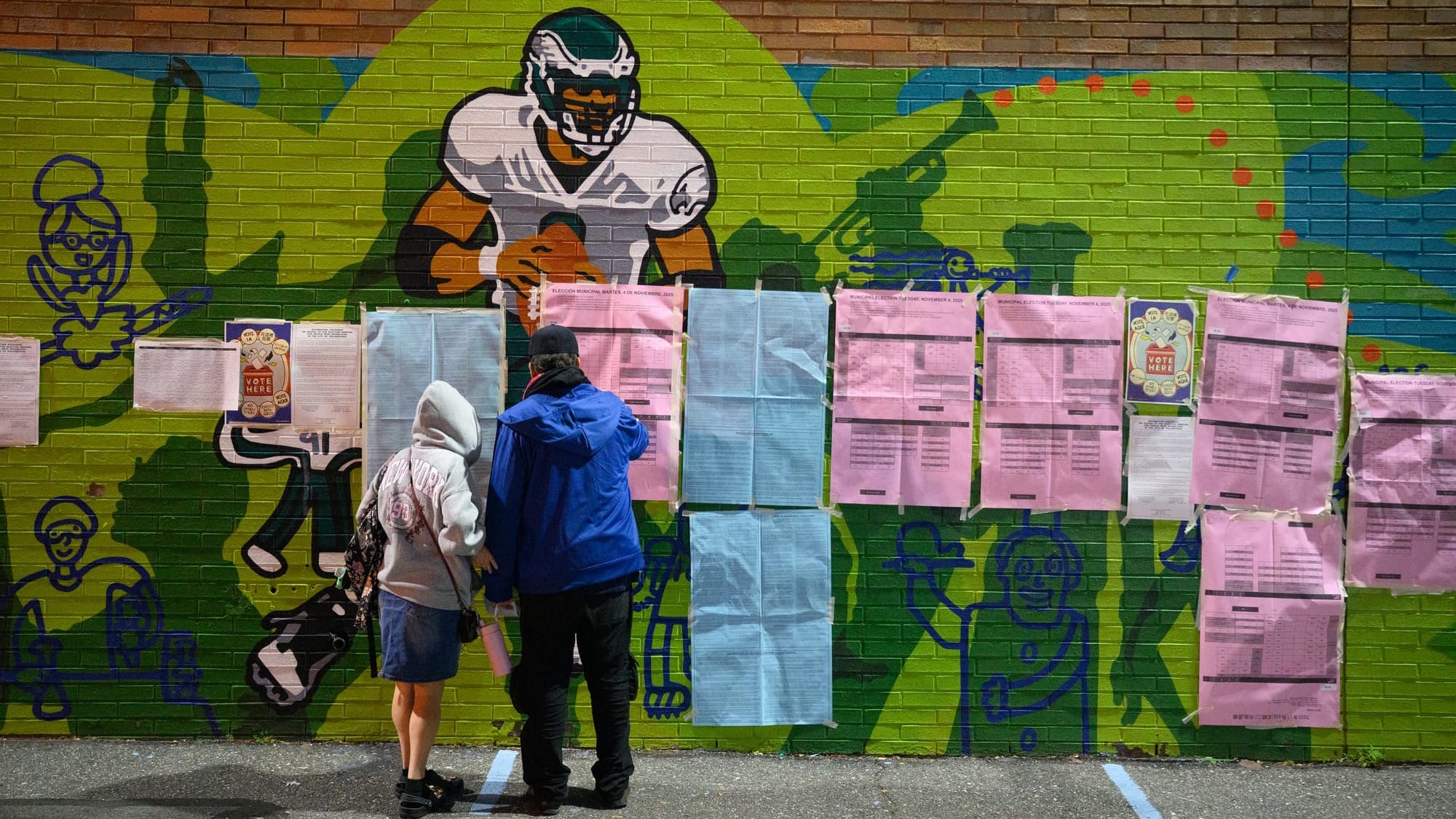

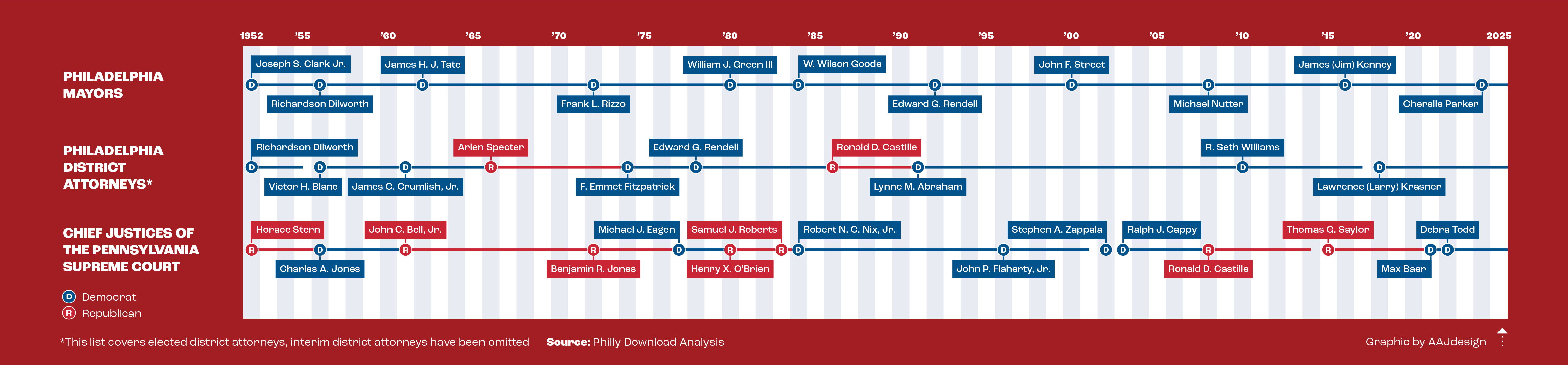

As the most populous city in Pennsylvania, Philadelphia —with roughly 1.58 million people— is an electoral powerhouse that can sway any statewide election in its favor, if all its residents choose to vote. For general elections like the one upcoming this November, under 22% of voters elected political candidates at the polls or submitted mail-in and provisional ballots in 2021. To make matters worse, less than 17% of registered voters participated in the May 2025 primary election. For Black Philadelphians who comprise roughly 39% of the city’s population, every election matters.

At the local level, this November 2025 election determining the city’s district attorney will define how the carceral system will operate in Philadelphia for the next four years. At the state level, this election will determine the protection or elimination of civil rights on issues like abortion, redistricting, and voting based on the retention or replacement of state supreme, superior, and commonwealth court judges who serve up to 10-year terms in office.

Like New York and Chicago, Philadelphia’s city budget allocates tremendous amounts of money to police. For Philadelphia’s 2024 Fiscal Year, the city’s budget was approximately $6.2 billion with $856 million slated to fund the police department and $293 million to fund prisons. Since 2021, Philadelphia’s homicide rate steadily decreased from 562 murders to 269 homicides in 2024. As of October 16, 2025, there have been 18066 homicides in the city, a 12.65.7% decrease from last year.

Time has shown us that as long as poverty, institutional racism, and social inequality rooted in anti-Blackness persist, our society will always be wrought with racial tension, violence, and crime. Ultimately, everyday citizens have the power to use this historical knowledge to guide them in social activism, protest, and voting to decarcerate and better Philadelphia for generations to come.